From ISI to Princeton and Back: Conversation with Ritabrata Munshi

SS: Hello sir, I am Swarnendu Saha from Team InScight, and it is an honour to have you with us today.

RM: Thank you. It’s a pleasure to be here.

SS: To begin with, could you take us through your journey of becoming a mathematician? Perhaps a brief overview of your academic path.

RM: Yes. It has always been my dream to be a mathematician. Even when I was very young, during my school days, I wanted to become either a mathematician or a theoretical physicist.

When I was in high school, I used to read my father’s journals. My father was an engineer and received journals from the Institution of Engineers. I was fascinated by the symbols—especially the mathematical symbols—that appeared in those journals. I loved looking at them and trying to understand what was actually going on. That curiosity gradually turned into a passion. Even in classes seven and eight, I started maintaining a diary in which I would write down mathematical ideas and thoughts.

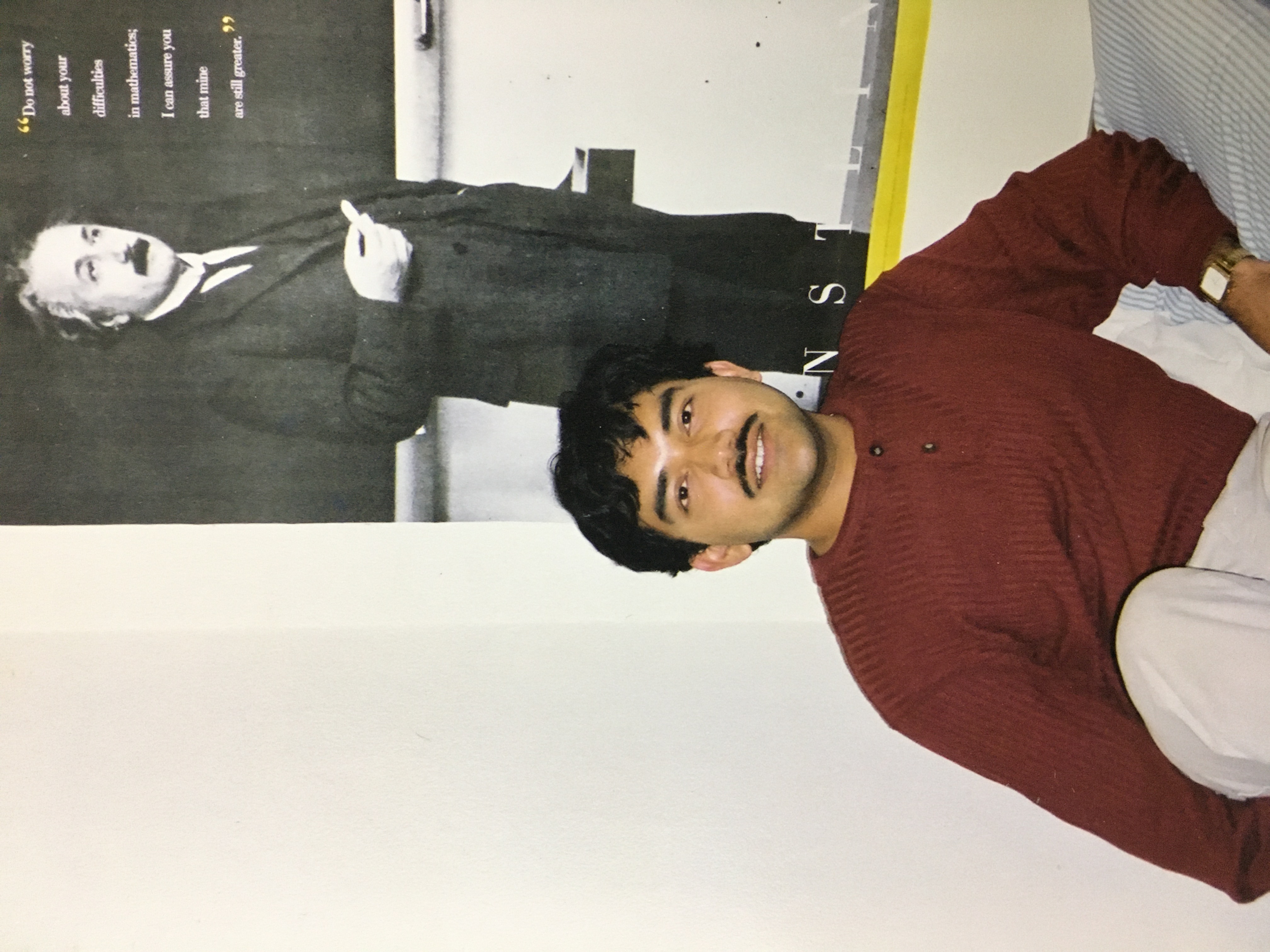

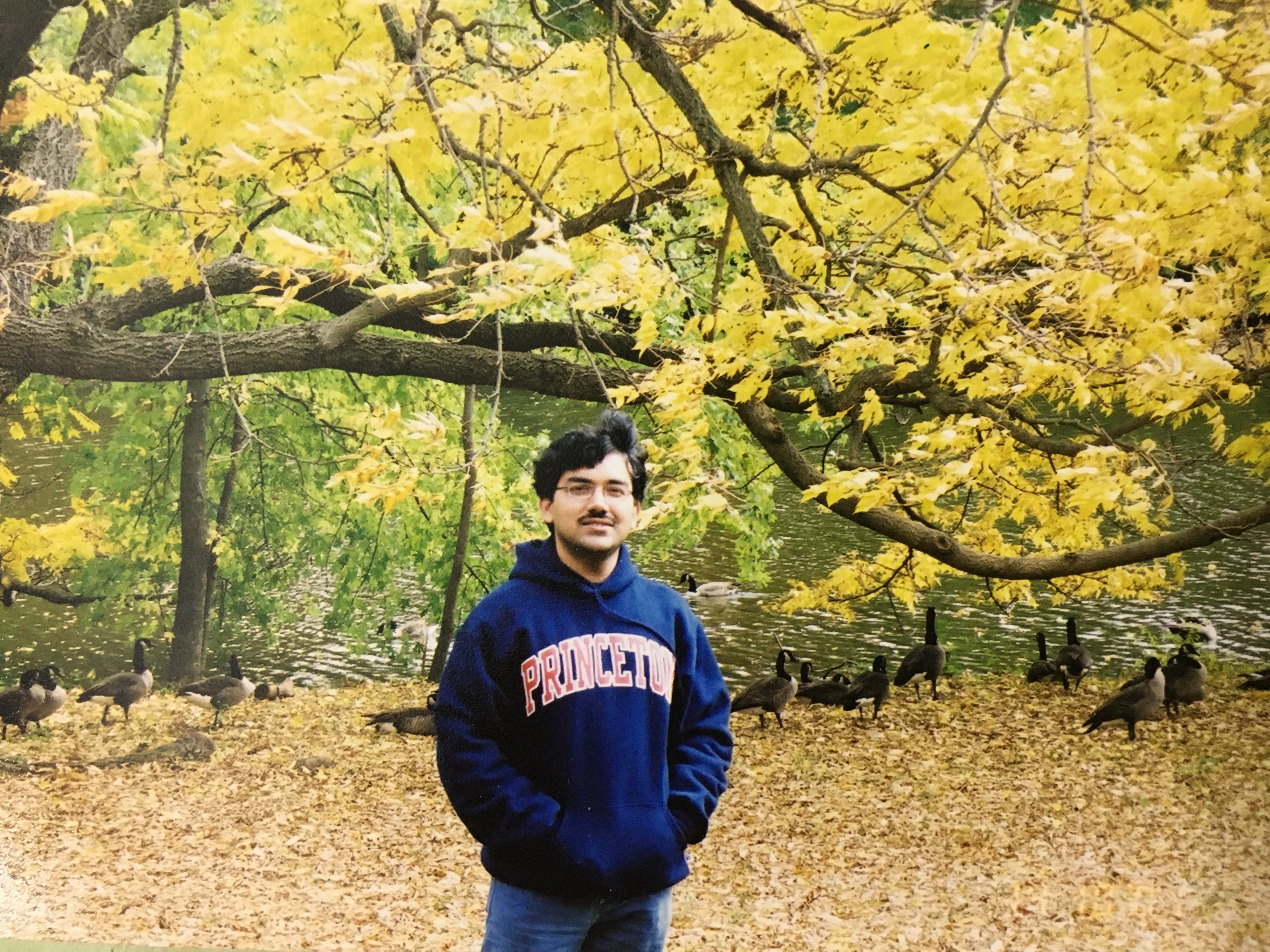

After finishing school, I faced an important decision—whether to pursue engineering, possibly through the IITs, or to study mathematics. For me, it was a clear-cut choice. There was no confusion. I chose mathematics. At ISI, I received excellent training in mathematics. In my view, it was—and still is—the best place to study mathematics. From there, my journey truly began. I later went to Princeton and worked under Andrew Wiles, which was a dream come true.

SS: At that point in time, since your father was an engineer, was there pressure on you to pursue engineering? Do you think it would have been an easier route, given the familiarity?

RM: No, actually, I think my parents realized quite early on that I was not really interested in anything apart from mathematics. I also used to draw and paint a lot, so those were the only two passions I had—mathematics and painting. So, for me, the choice was quite easy.

SS: So, you were a student at ISI?

RM: Yes, I was a student at ISI. I did B. Stat. and M. Stat.. There was no B. Math or M. Math back then. I did my B. Stat at ISI Kolkata—that was the only option at the time. For M. Stat, I completed the first year in Kolkata. The second year I did in Bangalore, because it depended on the specialization one chose. Since I was more interested in mathematics than statistics, I opted for advanced probability. For that specialization, I had to go to Bangalore.

SS: Today, you are a faculty member at ISI Kolkata, and you were once a student at ISI. Having experienced the same institute from two very different perspectives, how do you see it now?

RM: First of all, ISI has changed quite a bit. When I was a student—from 1996 to 2000—I was at ISI Kolkata. I returned as a faculty member in 2015. So, there is almost a 15-year gap between the two phases. A lot has changed. When I was a student, ISI was a very small place. There were very few students and very few faculty members. The focus was entirely on performance, education, and knowledge—nothing else. Now, there are many more students, and I think the diversity and variation among students have also increased. For instance, when I was a student, my batch had only 13 students.

SS: Thirteen. You mean, one and three ?

RM: Yes—thirteen. One and three. Now there are around fifty students. So you can imagine the increase in variation.

SS: So, roughly four times the size.

RM: Yes. Our batch was different—quite exceptional. In fact, one of my classmates is here today; he is now at the University of Georgia. I am meeting him after almost twenty years. It was a very small group, and we were very closely knit. We helped each other with studies and almost everything else. We all lived in the hostel back then. Now, most students stay outside campus. I think the atmosphere has changed. I find it difficult to precisely articulate what has changed, but something certainly has.

SS: Would you say the change has been for the better or for the worse—both from a student’s and a faculty member’s perspective?

RM: If you ask me personally, I would say that I would rather be a student in the 1990s than now. But this is a different generation, and their priorities are probably different. Back then, interaction between faculty and students was much stronger. Our professors were always very welcoming.

SS: And how is it currently? When I joined in 2020 at IISER Kolkata for my BSMS, my batch had around 200 students. When my juniors joined, it increased to around 230. In that context, you are saying that 50 students in ISI is a large number. But in many institutes, a single department has more than that many students majoring in mathematics. So why do you think 50 students at ISI is a huge number?

RM: I think the key point is how ISI was originally designed. ISI was built to function with small groups. It is not like an IIT or an IISER. The philosophy behind ISI was fundamentally different.

SS: How is it different? What was that philosophy?

RM: The idea was to have a very small, carefully selected group of students, and teachers who would devote a significant amount of time to training them. With larger numbers, that becomes difficult. You simply cannot have one-to-one interaction with everyone. Earlier, that level of interaction was possible.

SS: What is the current teacher-to-student ratio?

RM: I don’t know the exact numbers, but—

SS: I’m asking because if there are about 50 students, one would expect at least 20–30 faculty members.

RM: It’s about 50 students per batch in B.Stat. Then there is M.Stat and M.Math. So roughly, you are looking at around 150 B.Stat students, about 100 M.Stat students, and around 70–80 M.Math students. And then there are PhD students as well. I personally supervise seven PhD students.

SS: So altogether, it would be around 250 students or more.

RM: Yes, altogether. But another important point is that not all faculty members at ISI are involved in core teaching. For example, in the Statistics and Mathematics Unit, all professors teach at least one course every semester and are deeply involved. However, that is not the case in all departments, simply because it is not always feasible.

SS: When ISI was founded, as far as I understand, its primary focus was mathematics and statistics, right?

RM: When ISI was built, the main focus was statistics—and anything closely connected to statistics.

SS: Yet, interestingly, one of the few preserved dinosaur fossils in the Kolkata region is housed on the ISI campus. It’s quite old, and if I am not mistaken, it comes from the Tungabhadra Basin, discovered around the time of Tagore’s centenary. So ISI does not seem to be limited strictly to mathematics and statistics in the way we often perceive it. From both a student’s and a teacher’s perspective, how do you connect this broader academic presence? I’m trying to understand the background.

RM: Yes, ISI does have a Geology unit. In general, any discipline that has a strong connection with statistics finds a place at ISI.

SS: So how is geology connected to statistics?

RM: You can apply statistics to geology, anthropology, or almost any discipline. Wherever there are measurements, data collection, and the study of data and numerical distributions, statistics becomes relevant.

That is why, when Mahalanobis founded ISI, he had all of this in mind. His idea was that wherever statistics could be applied, that discipline should have a place at ISI.

There is also a unit of computer vision and pattern recognition. You need computers to perform statistical analysis, which is why there is a Computer Science Department. You need mathematics to develop the theoretical foundations of statistics, which is why there is a Theoretical Statistics and Mathematics Unit.

Statistics can be applied to quantitative economics—hence the Economics Department. It can be applied to the study of language—hence Linguistics. It can be applied to biology—so there are Biostatistics and Genetics units. In that sense, everything is connected.

SS: Were these developments already in place when you were a student, or did they come up later?

RM: They were already there. These ideas have existed since Mahalanobis’s time.

SS: So over the years, how do you see the growth and expansion of ISI in terms of education and academic research?

RM: Today, the primary focus is on four core subjects—Statistics, Mathematics, Economics, and Computer Science. These are the subjects for which ISI offers degrees.

However, when ISI was founded, the degree was only in Statistics. Mathematics was treated as applied statistics at that time. Over the years, other units have, in my opinion, lost some of their earlier significance. They were more central when Mahalanobis himself was around.

SS: So would you say there has been a decline in diversity at ISI?

RM: In a sense, yes—at least in terms of relative importance. Take mathematics, for example. Mathematics has become more important because it is now formally taught as a subject. For B.Stat and M.Stat, mathematics is essential, since it is a core component.

And now we also have B.Math and M.Math programmes. This has attracted more students who are specifically interested in mathematics. As a result, the Mathematics department has gained prominence.

SS: What is your primary field of research?

RM: Number Theory. Number theory is essentially the study of numbers—primarily integers. But the interesting part is not the numbers themselves; it is the structure they carry. Numbers have an additive structure—you can add them. They also have a multiplicative structure—you can multiply them. And number theorists are interested in understanding how numbers behave as you move along the number line—say along the positive integers—with respect to this multiplicative structure.

For example, consider divisibility. The number 1 has no divisors other than itself. The number 2 has no divisors other than 1 and 2. The same is true for 3. These are called prime numbers. But 4 is 2 × 2, so it has a non-trivial factor. Five is prime. Six is composite. Seven is prime. So primes appear irregularly, but they are fundamental. Prime numbers are the multiplicative building blocks of integers. Every integer can be written as a product of primes. What we are really interested in is understanding the interplay between the additive structure and the multiplicative structure of integers.

SS: What do you mean by “interplay”?

RM: As you move along the integer axis, you are progressing additively—you keep adding one. But at the same time, the multiplicative properties of numbers—such as primality and factorization—change in complex and fascinating ways.

Understanding this relationship is at the heart of number theory. Every step is essentially adding one. And what we want to understand is what happens to the multiplicative structure at each step—whether the number you reach is prime or composite.

SS: So in that sense, subtraction would just be adding minus one.

RM: Exactly—adding minus one. That also comes under the additive structure.

However, when studying multiplicative structure, it is not very important to look at negative numbers. One can restrict attention to positive integers, and the questions remain just as interesting. So, for example, you can ask: how many prime numbers are there? If you go up to a large number—say 10,000—how many primes are there below it? More generally, how many primes are there up to a number ?

We would like to have a formula for that. Gauss came up with a conjectural formula for this around 1796. He suggested that the number of primes less than or equal to x, is denoted by pi(x), is approximately $x\/log x$. This became a central problem in number theory, and mathematicians spent nearly 100 years trying to prove it. Finally, between 1796 and 1896, the problem was completely resolved.

What is remarkable is that, in the process of trying to prove this single statement about the distribution of prime numbers, mathematicians developed entirely new areas of mathematics. Complex analysis was developed, new applications of Fourier analysis emerged, and combinatorics and real analysis advanced significantly. In mathematics, we often say that the most interesting problems are those that generate more mathematics. This problem—understanding the distribution of prime numbers—did exactly that. It led to deep developments across multiple fields.

That is why prime numbers remain such an active area of research even today. As you can see, this conference itself is titled “Primes, Patterns and Propagation.” We are still deeply invested in understanding primes.

SS: When you started your career, as far as I remember, you wrote a proof of the Jordan Curve Theorem. In that regard, I have two questions. First, were you interested in number theory at that time, or did your interest develop later? Second, in the introduction to your work, it is mentioned that you were not very interested in computers at that time—has that opinion changed?

RM: Yes, I wrote a proof of the Jordan Curve Theorem during my first year of B.Stat. At that time, I was quite interested in topology.

However, my interest in number theory began even earlier. I remember that when I was in Class 10, while preparing for my board examinations, we went to the book fair and bought David Burton’s Introduction to Number Theory. That book fascinated me. It is written in a way that even school students can read and appreciate it, and it provides remarks and notes that connect naturally to higher mathematics.

That is really how my interest in number theory developed. Even before that, of course, I had read about Ramanujan—which is a fairly standard Indian student story. You read about Ramanujan when you are ten, you try to become Ramanujan, and by the time you are sixteen, you realize that you cannot become Ramanujan.

Regarding computers—yes, at that time I was not very interested in them. Back then, computers felt rather boring. Things have changed since then, and of course I have also aged over the last 25 years. But even today, if you give me a computer and a mathematics book or a mathematical problem, I will choose mathematics any day.

SS: Currently, ISI Kolkata is facing certain challenges. As a former student and now a faculty member, how do you see these changes? How might changes in the institutional structure affect research and academics, given that the community and resources largely remain the same?

RM: I sincerely hope that the new structure will not affect the academic functioning of ISI. Academically, ISI is doing very well, and it does not need changes in that direction.

Of course, we always need more resources to grow and develop. But my main concern with the proposed bill was the restructuring of the governing council and, more importantly, the academic council. The academic council is central to maintaining academic autonomy. Fortunately, in the revised or modified version of the bill, that particular aspect has been addressed, so I am more comfortable with it now. As for the governing council, some changes were expected—I had been hearing about such possibilities for some time. What impact these changes will ultimately have on ISI remains to be seen. It could turn out to be beneficial, or it could bring challenges. But my firm view is this: as long as the academic structure is left untouched, ISI will continue to function well.

SS: As we approach the end—perhaps the last five minutes—I want to ask you something specific. You completed your undergraduate and master’s education in India at ISI, arguably the best place for mathematics in the country, and then went to the United States for your PhD. How do you compare the study, training, and thinking in mathematical research between India and the West?

RM: Overall, the training in mathematics in India is quite good. In fact, if you compare an average Indian student with an average American student, I would say the average Indian is better placed mathematically.

SS: By “average Indian,” do you mean someone who has completed their bachelor’s and master’s from a public university?

RM: Yes. If you compare them with an average American who has done a major or minor in mathematics—especially if you include community colleges and exclude the very top universities—then I think the average Indian student stands higher.

However, the big difference lies in flexibility and freedom. In the US, if you are a promising student, you are strongly encouraged and given access to opportunities. From a very young age, students have access to resources, mentorship, and even university-level courses. You can talk to professors, attend college classes, and sometimes even fast-track your education.

You might start college-level mathematics at the age of 15. Mathematics is largely a subject for young minds—much like chess. When you are young, your mind is fresh, and that freshness is crucial for mathematics. So it is very important to identify talent early and guide it properly.

SS: One of my final questions—and you may disagree with me, or even get angry—is this. Many of us chose science over engineering or medicine and faced questions about that choice, given the current situation in the country. Now, after studying science, I want to ask you—someone who has devoted his life to mathematics—how do you see the subject today? Do you see it flourishing? Do you see students choosing it out of genuine interest, or merely as a degree? And more broadly, many people say that science—and especially mathematics—is a “dead” subject. What is your take on that?

RM: People say many things. That does not mean they make sense.

SS: It is our responsibility to explain what is correct.

RM: Exactly. Mathematics is one of the oldest human intellectual pursuits. You can trace it back to ancient civilizations—the Vedic period, the Babylonians, the Greeks. Mathematics has existed for thousands of years.

What is remarkable is that even after 2,000–3,000 years, it is still alive and thriving. People continue to work in mathematics and discover new results. How many other subjects can claim that kind of longevity?

Take artificial intelligence, for example. Do you think AI will survive for 2,000 years?

SS: It may evolve or transform.

RM: I don’t think it will survive in the same way. When I was deciding between engineering and mathematics, computer science, electronics, and information technology were “in fashion.”

SS: But those fields still exist, right?

RM: They exist, but not in the way they once did. The excitement, the structure, the focus—it has changed. Mathematics, on the other hand, has endured, although its prominence has not been uniform throughout history.

SS: By “not uniform,” do you mean temporally or subject-wise?

RM: Temporarily. If you look at ancient Greek mathematics—Euclid, Pythagoras, Archimedes—it was a golden era. Then there were periods with relatively little visible activity. Later, from around the 12th century onward, algebra and new mathematical ideas emerged. Again, there were quieter periods, followed by renewed bursts of activity.

SS: Why do you think this pattern exists? The need for mathematics—whether practical or intellectual—should always be present, shouldn’t it?

RM: I think before the Industrial Revolution, mathematics had limited application in everyday human life. After the Industrial Revolution, people realized how mathematics could be used to optimize systems, solve practical problems, and drive technological progress. But the Greeks were not doing mathematics because it was useful. Mathematics was, in a sense, a “useless” pursuit back then—or perhaps a better word is art. At its highest level, mathematics is art, not science.

SS: And that still holds—that higher mathematics is a beautiful but “useless” art?

RM: Yes, absolutely. So it remains. At the highest level, mathematics is purely art. There is no science in it—it is pure imagination. At the same time, mathematics is also the unifying language. It is the language we need to understand underlying reality.

SS: By reality, you mean—

RM: The universe, physics, and all of science. Mathematics is the correct language to describe them.

That is why mathematics has survived for thousands of years. I do not think it has lost any of its charm. In fact, I doubt whether many of the subjects that are fashionable today will survive even a hundred years. Things will change so much that people may forget them altogether.

SS: One final question. As an experienced mathematician, what would you like to say to younger students—those who have already taken up mathematics, those who are thinking of taking it up—and also to the general public?

RM: To students who are choosing mathematics, I would say this: you are making an excellent choice. But be prepared for a lot of frustration. Doing research in mathematics—especially at a high level—is like trying to move a wall. And when it moves, you are lifted to a completely different level. But most of the time, it does not move. So mathematics is, in some sense, 99% frustration and 1% success.

SS: So we have to enjoy the journey through that frustration?

RM: Exactly. The real joy of mathematics lies in the attempt itself—in trying to move the wall. That is where the fun is. When the wall finally moves, you feel immense satisfaction—but there is also a strange sadness, because the struggle that defined the journey has ended.