Seeing the World Mathematically: A Conversation with Prof. S. D. Adhikari

SS: Hello sir, I am Swarnendu Saha, and I welcome you to this interview session with InScight. My very first question is inspired by something a professor once told me: “Mathematics, in its highest form, does not remain science; it becomes useless—but fantastic—art.” What are your thoughts on this?

SDA: Actually, this idea comes from a quotation from Bertrand Russell. You’ve paraphrased it a bit differently, but Russell compared mathematics when rightly viewed as beautiful as a sculpture. He emphasized that mathematics is not only useful but also profoundly beautiful. Take the distribution of prime numbers, for instance. The pattern of primes in general, is beautiful in itself. There are many such patterns in mathematics that possess aesthetic value beyond utility.I once attended a lecture of Sir Michael Atiyah where the speaker posed an interesting question: Why does the external physical world follow mathematics? The answer given was that it is not the external world as it is, but the external world as it appears to us through our senses. Our senses are governed by logic and mathematical thinking. Therefore, the world appears mathematical to us—quite naturally.

SS: So, you mean to say that it is not mathematics governing reality, but rather our perception of reality that is mathematical?

SDA: Exactly—the world as it appears to us. Consider sound: it has frequencies, but we can only hear within a certain range. Frequencies below or above that range are inaudible to us. Similarly, many animals cannot perceive colors; for them, the world is essentially black and white.So reality is not necessarily what is, but what we are capable of perceiving. For example, if you wear yellow-tinted glasses, everything appears yellow. The external world remains the same, but your perception changes.

SS: In that sense, it resonates with Tagore’s words:

আমারই চেতনার রঙে পান্না হল সবুজ,

চুনি উঠল রাঙা হয়ে ।

আমি চোখ মেললুম আকাশে,

জ্বলে উঠল আলো”

(It is my senses which colour\ Emerald green and ruby red.\ I look at the sky – \ Light appears;)

SDA: Exactly. All thinkers have essentially said the same thing. It is all because of consciousness. If there were no consciousness, who would perceive anything? And beyond that—what would even exist? No one really knows. Reality varies depending on the way it is perceived. We see the world through the lenses of desire and fear. I desire something, and because of that desire, I fear losing it. Desire and fear are two sides of the same coin. Only when one transcends both desire and fear does one begin to see reality as it truly is. That is why yogis and jñānis perceive a world very different from the one we live in. They inhabit a world where there is only bliss.

SS: Because they have nothing left to seek.

SDA: Yes, and they are not afraid of losing anything. In a world where everything is constantly being destroyed, the one who perceives that which is underlying and indestructible—that person sees reality.As you see in Bhagavad Gita (Chapter 13, Verse 28):

Vinashyatsu avinashyantam yah pashyati sa pashyati

SS: My next question is this: often physicists and physics professors say that physics is the world itself, and mathematics is merely the language used to describe it. In that context, physics is reality, and mathematics is its language. How do you view this idea?

SDA: As I mentioned earlier, it can be said that way. But again, I’ll go back to Atiyah—Michael Atiyah. He spoke about this idea in some interviews; I don’t recall exactly where. He gave a simple analogy. Suppose two people come to a river. One person wants to cross it, so he jumps from one stone to another—this stone, then that stone—and eventually gets stuck midway. Then he notices that someone else has built a bridge connecting the stones, and he simply walks across using the bridge. The person who built the bridge is a mathematician. He is not merely trying to cross the river; he is constructing a bridge—often a beautiful one—from one stone to another. That bridge may or may not have immediate use, but it can become useful for someone who wants to cross.

Take Riemannian geometry, for example. When it was developed, the motivation was not application. Mathematicians were exploring ideas like modifying the parallel postulate, trying to understand geometry in different ways. There was no practical application in mind at that time. Yet later, it became central to physics. In general, anything that is beautiful tends to find application eventually. Recently, I was lecturing on the Davenport constant. It originated from problems in factorization within number fields. Much later, it found applications in proving results such as the existence of infinitely many Carmichael numbers. So one good idea often ends up being useful in many different contexts. Someone, somewhere, eventually finds a way to apply it to something else.

SS: So does that mean that mathematics in its purest form is not immediately applicable to reality?

SDA: There are two possibilities. Sometimes, you want to achieve a specific goal, so you create the necessary mathematics—that happens quite often. At other times, mathematicians pursue ideas purely for beauty, logical completeness, or structural consistency. Later, those ideas become useful—not necessarily in explaining nature as it truly is, but in explaining how nature appears to us. And that appearance follows a certain logical structure. Both approaches arise from the same source: the human brain. Mathematics is built from our intuition, just as our understanding of the world is shaped by how it appears to us.

SS: Let me shift the discussion slightly now. On a more personal note—how did you end up becoming a mathematician?

SDA: As I mentioned earlier, I was interested in both mathematics and physics. At that time—after passing Class 11—I was slightly more inclined toward Physics than Mathematics. In those days, there was no Class 12. We had Class 11, and then we directly went to B.Sc. I passed my school in 1973.

SS: My mother was born in 1971. (chuckles)

SDA: So, what happened next was this: I appeared for the entrance examination at B.B. College. In physics, I was placed 11th (1st on the waitlist), but they took only 10 students. In mathematics, however, I ranked first. So naturally, I joined mathematics. After about one or two months, two students left the physics program to join engineering. I was asked whether I wanted to shift. But by that time, I had already developed an interest in mathematics.

SS: And that’s when you continued with mathematics.

SDA: Yes, because earlier we didn’t really know what a subject truly contained. What we study as mathematics in school is very different. But once I encountered advanced topics—real analysis and other higher-level courses—I became deeply interested.

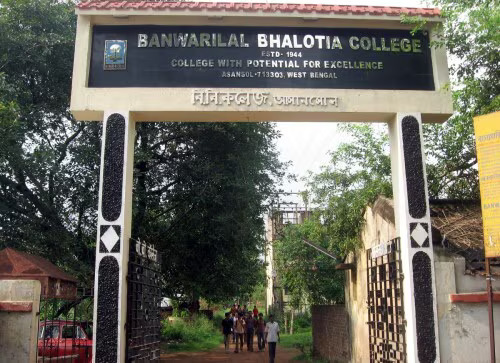

We were also fortunate to have some excellent teachers at B.B. College at that time. B.B. College refers to Banwarilal Bhalotia College in Asansol. I am still in touch with some of my teachers. Only one of the college teachers in Mathematics is still alive. He called me recently and wants to meet me—I’ll be visiting Asansol in February. He helped me immensely and had great affection for me. His name is Rammoy Haldar. He is now about 90 years old and lives in Asansol. If I forget to call him, he calls me himself. One of my chemistry school teachers is also still alive and lives in Durgapur. He, too, calls me. I shared a very warm relationship with my teachers.

SS: After completing your bachelor’s degree—where did you pursue your master’s?

SDA: I completed my master’s degree at Burdwan University. After that, I secured the first rank in Pure Mathematics and was awarded a fellowship.

SS: And you joined IMSc, Madras?

SDA: No. I received a fellowship at Burdwan University.

SS: For your master’s degree?

SDA: No, for my PhD. I joined Burdwan University for doctoral research. However, not much research activity was happening there at

that time. So I tried to move elsewhere and even explored the possibility of joining Chandigarh University. Then someone advised me to apply to TIFR. I joined TIFR, but after about two and a half years I found someone willing to be my supervisor; Professor Balasubramaniam gave me a few things to study. But soon after that, he was moving to Chennai, and fortunately, I was able to move in with him. That turned out to be very good luck for me. He was an exceptional teacher.

SS: Two and a half years?

SDA: Yes. I was on a TIFR fellowship during that period. I was studying and preparing—that was essentially what I was doing. Study.

SS: Coursework?

SDA: Yes—coursework, and also deciding which direction you want to pursue. Around that time, Professor Balasubramaniam returned from abroad and asked me to read certain material. As I said, shortly after that, he was preparing to shift.

SS: And you shifted with him?

SDA: Yes. He gave me that option, and I chose to go with him. In hindsight, it was a very good decision.

SS: Why do you think it was a good decision?

SDA: Because of the teacher—purely because of the teacher.

He gives a lot of freedom and a lot of encouragement. He allows you to work independently, and at the same time, he helps you exactly when it is needed. Even now, I remain in touch with him. I visited him again in August when I went for a family function—he invited me, and I went. I also met him again in Chandigarh during an event connected to Professor Bambah. There was a conference organized in Professor Bambah’s honor, where about twelve people were invited speakers, all of them are rather senior. Among them were Professor Balasubramaniam, Professor Raghunathan, and Professor Kulkarni, who was a former director of HRI, Allahabad. Professor Kulkarni was 83, Professor Balasubramaniam was 75, Professor Raghunathan was 84, and I was 69. Professor Bambah passed away in May 2025, about four months before his 100th birthday. So the conference was held in his memory, and I met Professor Balasubramaniam again there, on September 30.

SS: At one point, you mentioned that you joined TIFR and spent about two and a half years doing coursework etc. before moving to Chennai. But that reading phase alone wasn’t for two and a half years, right?

SDA: No, the two and a half years include everything—coursework and preparation for research in Number Theory together.

SS: So how much of that time was purely coursework? Around two years—that’s what I was trying to clarify. Now, when students like me, my juniors, or my immediate seniors look for PhD positions around 2025, things are quite different. There are SOPs, structured projects, and in Europe or Germany, for example, PhDs are often three-year project-based positions where you apply directly to a defined topic.

SDA: Yes, things have changed a lot. I also received a fellowship offer from the US at that time, but I didn’t go because I already had a good guide by that time.

SS: So how do you see this change? You joined through a program, did coursework, and then spent about two years on research.

SDA: After moving to Chennai, I finished quite quickly and worked intensely. To some extent the degree got delayed due to the formal requirement that my guide had to be registered at Madras University. After that I received a postdoctoral position at TIFR again and after about one year I left for ICTP, Trieste. After that, I returned and became an NBHM postdoctoral fellow.

SS: National Board of Higher Mathematics ?

SDA: Yes—an NBHM postdoc at SPIC. At that time, CMI was known as SPIC. After that, I joined what is now the Harish-Chandra Research Institute.

SS: Which was earlier known as the Mehta Research Institute.

SDA: Yes, MRI at that time.

SS: So how do you see the changes in mathematics academia in India—from when you were a student to today?

SDA: Today, there are many more institutes. Before Professor Balasubramaniam moved to Madras, Prof. E C G Sudarshan came in and took over as its Director and at his invitation, Prof. C. S. Seshadri was taking care of Mathematics. But overall, the academic ecosystem has expanded significantly.

SS: I’d like to move to a different topic. I’ve heard that Pāṇini’s grammar in Sanskrit is often viewed by scientists and mathematicians as a sophisticated collection of algorithms.

SDA: Yes, it is extremely mathematical. I attended some lectures at RKMVERI, where there is a strong Sanskrit department.

Mathematicians gave lectures connecting Sanskrit grammar and mathematical structure. I am interested in Sanskrit, but I haven’t studied its grammar in depth. Still, it is undeniably very mathematical.

SS: At its core, it’s about logic, right? Could you explain that briefly for students?

SDA: I wouldn’t want to explain something I only partially understand. I know a little, but not enough to do justice to it.

SS: Let me ask about your academic work. After your postdoctoral years, what was your main research area?

SDA: My PhD was in analytic number theory, which I continued working on for some time. Later, I began working on combinatorics and what I lectured on today—additive and combinatorial number theory. I also did some work in transcendental number theory. Over time, I worked across four or five areas within number theory. But what I enjoy most are elementary methods. Elementary does not mean easy. It means avoiding heavy machinery like complex analysis or abstract algebra, and instead using real analysis, combinatorial reasoning, and first principles.

SS: From first principles.

SDA: Yes. Paul Erdős is my hero. I was fortunate to meet him in Hungary. I spent five days talking to him extensively. He gave me some problems, I wrote in my notebook, and I even spoke to him once on the phone later while I was in France.

Sadly, he passed away soon after that. Otherwise, we might have written a joint paper. Still, I have papers with people who themselves have papers with Erdős.

SS: Could you briefly explain the subjects you’ve worked on, for students?

SDA: At present, my main focus is combinatorics. The core combinatorial tools are induction and counting. These methods are used across many areas of mathematics. At the same time, combinatorics now borrows tools from topology, algebra, probability, and ergodic theory. For example, Szemerédi’s theorem—originally conjectured by Erdősand Turan —was first proved using difficult but elementary combinatorial methods.

Later, Furstenberg gave an ergodic-theoretic proof. I even organized an Ergodic Ramsey Theory workshop in Pune in 1997 and invited Bergelson, a student of Furstenberg. So while my main strength—my “bread and butter”—is combinatorial thinking, I actively keep track of developments in other approaches. I sometimes use algebraic tools in combinatorial proofs as well.

SS: Let me bring the discussion back to the physical world. Earlier, you used the analogy of someone building bridges and someone else using them. But can combinatorics be directly involved in the material world?

SDA: Many mathematical questions arise from very natural curiosities—such as how many ways something can be done. At the school level, this is basic combinatorics. As these questions become more sophisticated, they find strong applications, particularly in computing. Combinatorics is extremely useful. I teach a course on it, and many students from computer science want to attend. In some years, the entire computer science batch attended the course along with mathematics students. Combinatorics has flourished over the last few decades largely because of its applicability to computer science. In many ways, computer science is combinatorics.

SS: Given this close connection between combinatorics and computer science, today we hear a lot about artificial intelligence. Does AI research also rely on combinatorics?

SDA: Yes, AI certainly uses combinatorics. But there is an important distinction. Artificial intelligence works by following algorithms—algorithms that humans already know how to design. If I already know that choosing one path is less costly than another, I can encode that information and feed it into an AI system. The system will then follow those instructions efficiently. But when something genuinely new is required—when a new idea or a new algorithm has to be discovered—that still requires the human brain. Machines can perform calculations faster. They can add, multiply, and even make logical decisions very efficiently. But those decisions are based on prior human knowledge. The act of probing, analyzing, and discovering something new—that creative step—comes from humans.Computers are extremely useful for data collection and implementation. But the step from raw data to deep understanding often needs human intuition. That does not mean humans will be replaced entirely. For example, if there is radiation leakage inside a nuclear reactor, humans cannot go inside safely. We use robots to perform such tasks. In that sense, technology protects human resources rather than replaces them.

SS: But do you think that today mathematics—especially abstract mathematics—is not directly feeding the masses in a material sense, and therefore may not be attracting new generations?

SDA: No, no—that is not the right way to frame it. There is a famous line of poetry—by Satyendra Nath Datta—

জোটে যদি মোটে একটি পয়সা খাদ্য কিনিয়ো ক্ষুধার লাগি’

দুটি যদি জোটে অর্ধেকে তার ফুল কিনে নিয়ো, হে অনুরাগী!

(If you have one coin, buy food to satisfy hunger.\ If you have another coin, buy flowers to nourish the soul.)

First come necessities—food, shelter, daily needs. Mathematics certainly serves these needs today through computers, technology, and applications. After that, if time and energy permit, we also explore ideas driven by logic and beauty. And those ideas often become useful later. What is done today purely for intellectual beauty may find applications tomorrow. Take number theory—Hardy famously believed it would never be used in war. Today, number theory is fundamental to cryptography and coding.At the time, Hardy took pride in the fact that his work had no military application. But history turned out differently. The point is: you never know when a good, logical, or beautiful idea will become useful, or where it will be applied. Sometimes it is used in areas for which it was never intended. Even within mathematics, ideas developed in one field often become powerful tools in another. Algebraic concepts are frequently used to solve problems they were not originally designed for. That is how mathematics grows—and why it remains both meaningful and indispensable.

SS: So, would you say that a lot of this is a matter of luck and chance?

SDA: Yes—many things do involve chance. Someone happens to encounter a particular conjecture. If they hadn’t seen it, they might have worked on something entirely different. Perhaps they were exactly the right person to solve that problem. In the world, many such chances are constantly at play. Suppose there are ten people who are all capable of solving a problem. Only one of them happens to meet the right question at the right time. The other nine could also have solved it, but they never encountered it. There are many people who stop formal education, yet they have tremendous potential. It’s like farming—you need good soil, sunlight, and water. Even good soil may fail to produce anything if it doesn’t get water.

SS: Following that, let me raise another concern—especially relevant to Bengal, where I have some data. In general science, and particularly in core subjects like physics and mathematics, fewer students are enrolling nowadays.

SDA: There are two aspects to this. One concerns teachers—but I won’t go into political aspects of selection. If teacher selection is done properly, we get motivated teachers. If I am not motivated, how can I motivate you? If I am teaching only for money, I cannot inspire students. But if I genuinely love the subject, that love naturally gets transmitted. Of course, not every student has that spark—but even if a student does have it, an unmotivated teacher can kill it. Also, teachers are not only those who stand in classrooms. A good book can be a teacher. An experience can be a guru. And something must exist inside the student. Ramanujan is a perfect example. He found Carr’s Synopsis and discovered patterns and beauty on his own. But something inside him drove that exploration. Later, he was recognized and supported. If that recognition hadn’t come, his story might have ended very differently.

SS: Ramanujan would not have been Ramanujan.

SDA: Exactly. Had Ramanujan gone through conventional mathematical training too early, perhaps he would not have been Ramanujan either. He might have been forced to think like the rest of us, without the freedom to think in his own way. Initially, he was allowed to explore freely. Later, structured training supported him. That combination was optimal. As Nisargadatta Maharaj once said, for anything to happen, the whole world must coincide. Nothing happens in isolation—everything must support it.

SS: At IISERs, we see batches of 200–250 students across subjects, but mathematics has the fewest enrollments. One reason seems to be the job market.

SDA: Yes, employment plays a role. Students see their seniors completing five years of PhD and still struggling for stable jobs. Even if they love mathematics, survival matters. So many students move into data science after an MSc in mathematics. The question then becomes: Can mathematics feed people? But “feeding” doesn’t only mean immediate money. Teaching positions in schools and colleges are essential, but many posts remain unfilled, funding is limited, and selection processes are sometimes flawed. Minimal institutional support is crucial. Without it, even good students struggle.

SS: In that context—what makes a good teacher?

SDA: A good teacher must first be a good student.

I don’t believe in the strict division between teacher and student. There are only senior students and junior students. Everyone is learning. The moment I stop learning, I stop being a teacher. A teacher must have burning enthusiasm—to learn, to explore. In a classroom, I can only teach for a few hours. But if I genuinely see the beauty of the subject, you will see it in my eyes.

SS: So you see yourself as a student?

SDA: Absolutely. Everyone is a student. Otherwise, all problems would already be solved.

SS: You mentioned unsolved problems. Have you devoted significant time to such problems yourself?

SDA: Yes, yes—I have been fortunate. I’ve solved or substantially contributed to some good problems.

In one case, I worked with my teacher Professor Balasubramaniam on a conjecture—not during my PhD, but later. The conjecture was resolved, though gaps between upper and lower bounds remained. Later, in higher dimensions, I worked with Yang Gao Chen, whom I met in Hungary. In two dimensions, I worked with another group. Later, with Andrew Granville in Canada, we more or less resolved the problem in dimension two.

SS: Can mathematical problems truly be solved completely—like “two plus two equals four”?

SDA: Some can. Fermat’s Last Theorem was solved. Waring’s problem was solved. Van der Waerden’s theorem was solved. Szemerédi’s theorem—originally conjectured by Erdős and Turán—was solved. But once you solve a problem, you generalize it—and the generalization becomes a new problem. Mathematics never really ends. Szemerédi proved the theorem using difficult but elementary combinatorial methods. Later, Furstenberg proved it using ergodic theory. Different methods, same truth.

SS: You’ve quoted many philosophical figures during this conversation.

SDA: Not monks—I quoted the Gita and Nisargadatta Maharaj. He was not a monk; he was a householder in Maharashtra. Maurice Frydman—an engineer who knew many languages—recorded Nisargadatta’s teachings and later became a monk. Nisargadatta did not.

SS: You’re currently affiliated with Ramakrishna Mission institutions. Have these philosophies influenced you?

SDA: I’ve been reading such texts since Class 10. Not only Ramakrishna—also Ramana Ashram,Tiruvannamalai and Pondicherry Aurobindo Ashram . Advaita Vedanta resonates deeply with me. But philosophy is like swimming. Reading books won’t make you a swimmer—you must jump into water. Books like are maps. Walking the path is realization. To realize the truth, one must go beyond desire and fear.

Drishtim jnanamayim kritva pasyet brahmamayam jagat.

We all wear spectacles of desire and fear. Clean them—and reality appears.

SS: How does this help you as a mathematician?

SDA: It teaches detachment. If I get a good result and become complacent, someone else may move ahead. If I fail repeatedly and become dejected, I may miss success just one step away. So neither excessive happiness nor excessive sadness helps. One must simply keep working. As I have already mentioned, Faiz said it beautifully: the journey itself is success. If you fix a destination and fail to reach it, you feel defeated. But if walking itself is the goal, you are always successful. That is karma yoga.

SS: You seem to enjoy learning languages as well.

SDA: Yes. I learn French every morning. I improve my Sanskrit every evening.

That’s why I say – everyone is a student. There is no final teacher.

SS: Did you spend time abroad?

SDA: Yes, many times. I stayed in Italy for about two years. After that, I kept visiting Europe for one or two months at a time. I have also been to the US, Canada, China, and Japan. In fact, I have visited almost all continents — Australia, South Africa, South America. I have good friends and collaborators in many places. For instance, during Durga Puja 2025 I was in Spain. After a two-day conference in Chandigarh, I came to Delhi and then flew to Barcelona. There, we completed a piece of work we had been pursuing for nearly a year. In July, I went to Austria—specifically to the University of Graz. There was a conference at TU Graz, and I also visited other universities. Last year again, I visited Barcelona and the Hungarian Academy. I still manage to travel to some extent. In March, I am going to Rome to visit an old collaborator, Francesco Pappalardi, who was a student of Professor Ram Murty. On the way, I will lecture at IIT Delhi, and on the way back I will lecture in Ashoka, as I have friends there and enjoy meeting people.

SS: Where do you stay now?

SDA: I stay on the campus of RKMVERI, near Belur Math.

SS: And your home?

SDA: I have a flat, and I also have a place where I meet people. Coming back to your earlier point, since I have visited many places, including very large institutes like IHES, Paris and Princeton University, I have met some of the top mathematicians in combinatorics. One of the greatest figures for me is Erdős—he is my hero. I was lucky to meet many people and interact with them. For example, I met Schmidt, a great expert in transcendental number theory, several times in India and Europe and he later invited me to Colorado.

SS: How does it feel to meet such great people and interact with them?

SDA: If you think someone is superior to you, you develop an inferiority complex. If you think someone is inferior, that is another kind of complex. But if you have no complex at all, then what is the problem? I respect those who know more than me and learn from them. If someone is thinking a bit slowly, I help them. Everybody is learning, and we help one another.

SS: But you called Erdős your hero.

SDA: Yes, a hero in the sense of his nature. He was always thinking about mathematics. He carried only a small bag and traveled constantly. Whatever money he got, he gave to poor students. Even if someone wanted to return the money after getting a job, he would pass it on to another needy student.

SS: Pass it on!?

SDA: Exactly—pass it on. He would take students out to dinner and spend the money on them. He had no fixed place to live—only mathematics. He wrote 60–70 good papers a year. Many ideas in probabilistic number theory originated from Erdős. If you read the book by Halberstam and Roth on sequences, you will see how much came from Erdős’ questions and work. He and Selberg proved the elementary proof of the Prime Number Theorem. Despite all this, he had no arrogance. He spoke to me very naturally. Once, we were chatting, and after some time he politely said he would take a short rest. I went for coffee and came back—he was already working again. He never said, “Don’t waste my time.” Such humility.

SS: Do you still have students?

SDA: My PhD students have completed, but I still work with people—through collaborations.

SS: How do you see the difference between academia in India and the rest of the world?

SDA: India is doing well. I am not saying otherwise. But in many places abroad, facilities are better—especially libraries. In India, some institutions lack strong libraries, though the National Board of Higher Mathematics (NBHM) has been trying to help by sending books and providing financial support. I served on the NBHM library committee for many years and was associated with NBHM for about 12 years. I know they contribute significantly. Senior mathematicians also initiated programs like MTTS (Mathematical Training and Talent Search), started by Prof. Kumaresan, and later senior student training programs under NCM. I was involved in MTTS for many years and taught there. Many people have contributed—some far more than me.

SS: Do you think going abroad for higher studies helps in returning to Indian academia?

SDA:Going abroad helps because you meet people and exchange ideas. Two brains working together often lead to results. For example, I once shared an idea with Ruzsa. He was listening casually, but Chen picked it up immediately and said it was correct. That led to a paper. However, I don’t fully agree with the idea that foreign degrees should automatically carry more weight. Some people have done excellent work entirely in India. We have very good guides and teachers here.

SS: What is NBHM?

SDA: NBHM stands for the National Board of Higher Mathematics. They provide postdoctoral support, travel grants, faculty funding, books for libraries, and organize training programs. They support MTTS and advanced workshops through NCM. The Board was initiated by Prof. M. S. Narasimhan, followed by Prof. Raghunathan and others. Many of us were involved at different stages.

SS: How were your days at the Harish-Chandra Research Institute?

SDA: After DAE took over, I was among the first group to join. “First” here means four people were selected. One person joined after a month, but I happened to join first. So, in terms of station seniority, I was superior to everyone else. After the age of 60, I received a two year extension (with possibility of another two). But I left after six months and I came here to RKMVERI.

SS: How are the research lives at HRI and RKM different?

SDA: Progress is happening. Sometimes it is visible, sometimes not. But underneath, there is always some progress. Funding is an issue, of course. I think gradually private initiatives should also take responsibility. In the US, many excellent universities are private. In India too, that culture is coming up, and I don’t think it is necessarily bad. Institutions like Ashoka University in Delhi, Shiv Nadar University, SRM, and others are private. Even Lodha has invested. Professor Kumar Murty is there—very good people are taking care of these institutions. Not everything will work perfectly from the beginning, but over time things will improve. Interactions will increase. Many senior mathematicians like Ram Murty and Kumar Murty frequently came to India and took students abroad. I visited them there, and many people benefited from long-term visits. One chapter of my PhD thesis was actually suggested by Ram Murty, who used to come every year to Chennai to lecture. He was a friend of my guide.

SS: As a teacher, what do you look for in a student who wants to work with you?

SDA: First and foremost, the subject must be natural to that person. I try to see whether their thinking is natural for mathematics. Sometimes a person may be very capable, but meant for something else. Second, the person must be hardworking and motivated. If that initial spark is there, I can help motivate further. But if the basic inclination is missing, I cannot push it. You see, if you take a square object, no matter how much you kick it, it won’t roll. But a round ball will. So that initial nature matters. Everyone has some talent. I believe that in nature—God’s world—everyone is meant for something. You have to discover what that is and follow it. By doing work that is natural to you, you are worshipping that work. And that itself is worship of God. As Bhagavad Gita (BG 18.46) says

Swakarmana tamabhyarchya siddhim vindati Manavah.

So work—work incessantly, as Swamiji said—but do not bind yourself. Bondage is terrible. Working with expectations of praise, success, or recognition creates bondage. Success will come. Failure will come. Praise will come. Criticism will come. You continue working and enjoy the work itself. That is what Faiz also said:

Faiz thi raah sarbasar manzil

Hum jahaan pahunche kaamyaaab aaye.

SS: Finally, what would you like to say to upcoming mathematics students?

SDA: When I enter a classroom, I stand with folded hands—internally. You never know who is sitting in front of you. That person may become a great mathematician in the future, perhaps far greater than me. You are initiating someone into a subject. You don’t know who will become what. So one should always remain humble, with folded hands before the miracle of God. We are doing very little, really. But this attitude helps both yourself and others. There should be no aham—no ego. An egoistic person thinks, “I did this.” But in reality, I met the right person, I encountered the right question, someone else gave the right input, and together we solved it. So where is “me” in this? If nature is doing everything, I am only an instrument.

SS: Thank you sir for your time with us. We truly believe our readers shall have a great time to spend some time with you through the pages of InScight. With that thought, we end today’s discussion. Thank you.