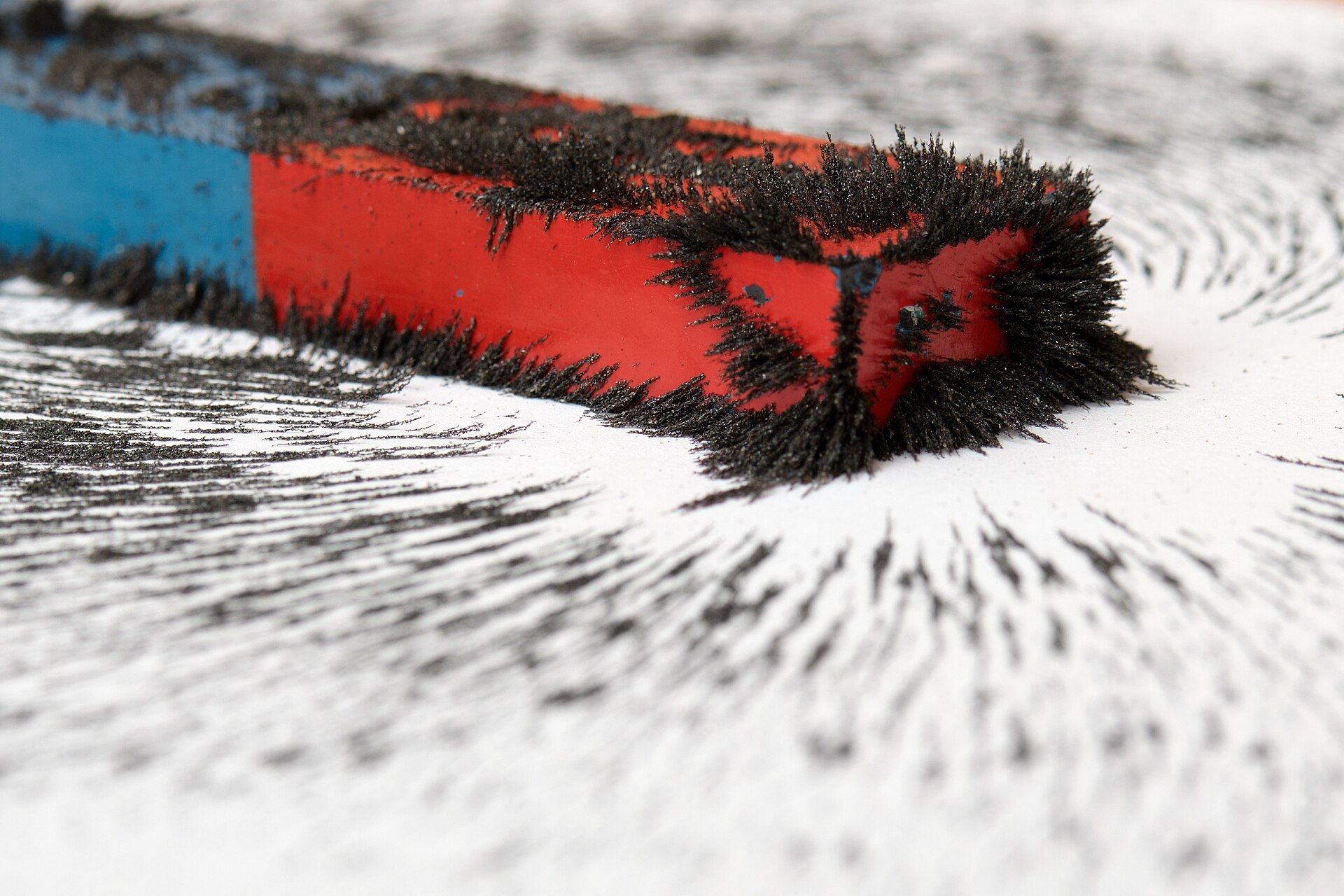

The early 20th century was a major turning point in physics, often considered the birth of modern physics. It marked a fundamental shift away from the classical worldview that had dominated since Newton. Classical physics (Newtonian mechanics, Maxwell’s electromagnetism, and thermodynamics) worked well for everyday phenomena, but it failed at extreme conditions: ”Couldn’t explain the behavior of light and matter at atomic scales”! One such roadblock was faced by none other than Niels Bohr in 1911. Bohr found that classical electron theory was fundamentally inadequate to explain observed magnetic properties, such as the Hall effect(The development of voltage across a current-carrying conductor placed in a perpendicular magnetic field). Through his rigorous application of classical principles, he demonstrated that, in thermal equilibrium, the net magnetization of a collection of electrons would always vanish. This implied that phenomena like paramagnetism, diamagnetism, and ferromagnetism could not be explained by classical physics alone(10)! Isn’t it fascinating that a seemingly classical, age-old phenomenon like magnetism could actually have a fundamentally nonclassical explanation (Fig. 1)?

Eight years later, Hendrika Johanna van Leeuwen independently derived the same theorem in her 1919 doctoral thesis, thus the result is now formally known as the Bohr-Van Leeuwen theorem (4). Notably, she was unaware of Bohr’s prior discovery. Her research similarly concluded that classical physics and statistical mechanics could not account for the existence of magnetism, emphasizing its quantum mechanical nature.

This independent convergence on a critical result powerfully validates the idea, thereby compelling the scientific community to seriously consider and develop alternative, non-classical frameworks.

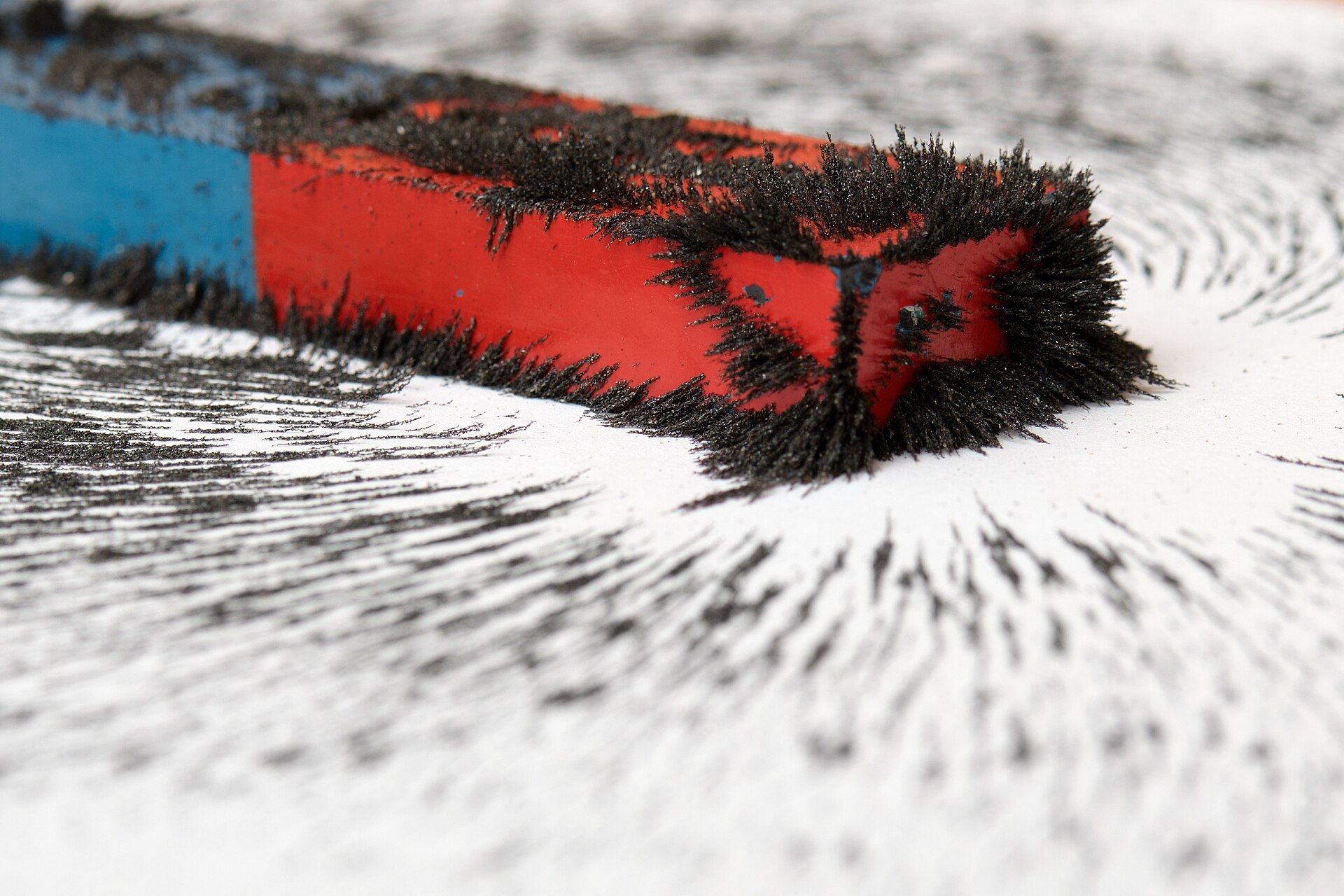

When classical physics fell short, Niels Bohr sparked a revolution in 1913 by proposing that electrons don’t whirl randomly around the nucleus — they jump between fixed orbits like steps on an invisible ladder. These quantized orbits gave atoms their stability and hinted at the origin of magnetic moments. Arnold Sommerfeld later in 1916 added elegance to Bohr’s sketch, allowing electrons to follow elliptical orbits and even move relativistically!! (11)

Given that classical physics forbids spontaneous magnetization in equilibrium, one might wonder how magnetization was nevertheless described successfully for decades? Where did the ignorance sweep in? Let’s see an example. Paul Langevin’s 1905 theory of paramagnetism(weak attraction of materials to magnetic field due to unpaired electrons aligning with it), embodied by the Langevin function, is historically regarded as a classical approach. It was developed before the widespread acceptance of quantum physics and relied solely on classical concepts like Boltzmann distribution for alignment in an external magnetic field. But how did he get paramagnetism classically?

The ”borderland” nature of the Langevin function arises from Langevin’s implicit ”quantization” of the system. As J. H. Van Vleck famously observed, ”When Langevin assumed that the magnetic moment of the atom or molecule had a fixed value, he was quantizing the system without realizing it (1)”. This assumption of a fixed, discrete magnetic dipole moment, rather than a continuously variable one, aligns with a quantum mechanical perspective where certain physical properties are quantized. This ”accidental quantization” in Langevin’s work is a fascinating historical and conceptual point. It suggests that the empirical observations of magnetism were already subtly hinting at the discrete, quantized nature of physical properties, even before the formal development of quantum mechanics. Interestingly, in that same year (1905), Einstein introduced the concept of the photon through his paper on the photoelectric effect, marking the true beginning of quantum theory.

Theorem (Bohr-Van Leeuwen). At any finite temperature, and in all finite applied electric or magnetic fields, the net magnetization of a collection of electrons in thermal equilibrium vanishes identically.

$ chevron.l mu#sub(“tot”) chevron.r = frac(e,2c)Sigma_i chevron.l r_i times v_i chevron.r = 0, $

where

The Bohr–van Leeuwen theorem (Bohr, van Leeuwen) shows that if one applies classical mechanics together with classical statistical mechanics to an ensemble of charged point particles (using the usual Hamiltonian with kinetic energy and Coulomb/Lorentz forces and Maxwell–Boltzmann statistics), the thermal-average magnetization vanishes. In other words, classical point-particle statistical mechanics — without any additional structure — cannot produce the orbital contributions to diamagnetism or paramagnetism, that is, the magnetic effects arising from the orbital motion of electrons around nuclei, which in quantum mechanics manifest as diamagnetic and paramagnetic responses. By contrast, phenomenological classical models that assume pre-existing magnetic moments (for example, fixed magnetic dipoles or rigid extended current loops, or models built from a continuous/extended charge distribution) are not within the strict assumptions of the theorem: they start by postulating a magnetic moment or current distribution and therefore can yield nonzero magnetization and reproduce results such as the Langevin susceptibility (Curie’s law) for an ensemble of permanent dipoles.(27) The crucial distinction is therefore one of assumptions. The Bohr–van Leeuwen result does not say “classical physics cannot describe any magnetic phenomena”; rather it shows that classical point-particle Hamiltonian mechanics + classical statistical mechanics, taken literally, cannot derive magnetization — you must either introduce extra (and effectively quantum) ingredients (intrinsic magnetic moments, quantized angular momentum, exchange interactions) or relax the theorem’s assumptions (e.g., allow rigid extended currents, constraints, or non-equilibrium/rotating systems). (10)

3 July 1887, The Hague (Netherlands) – 26 February 1974, Delft (Nether lands) Daughter of Professors Pieter Eliza van Leeuwen and Maria Wilhelmina Schepman, studied secondary education in her hometown, and con -tinued her training in physics at the University of Leiden, under the supervision of Hendrik Antoon Lorentz. In 1919.(2) She obtained her PhD, her thesis entitled ”Problems of the electronic theory of magnetism” focused on explaining why magnetism is essentially a quantum mechanical effect (a result now known as the Bohr-van Leeuwen theorem). In this respect, Van Leeuwen was unaware of the results presented 8 years earlier by Niels Bohr also in his doctoral thesis (4). Fig 3. Hendrika Johanna van Leeuwen (1887-1974). (3)

We will see a non-formal explanation here, it begins by considering the system’s energy distribution as predicted by Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics, which is proportional to $exp(−U / (k_B T))$, where $U$ is the total energy (kinetic plus potential). A crucial step is recognizing that the magnetic field ($B$) does not contribute to the system’s potential energy. This is because the Lorentz force ($F = q(E + v times B)$), while dependent on the magnetic field, does no work on charged particles ($F dot v = q E dot v$, which is independent of $B$).

Consequently, the total energy of the system remains independent of the magnetic field, which in turn implies that the statistical distribution of particle motions is also unaffected by the magnetic field. In the absence of an external magnetic field, and given the constraint that the system cannot rotate, there is no net ordered motion of charged particles, resulting in an average magnetic moment of zero. Since the distribution of motions and thus the energy are independent of the magnetic field, the average magnetic moment, being zero in a zero field, must remain zero in any applied magnetic field.

While the theorem’s summary as ”no classical magnetic susceptibility, in particular no diamagnetism(magnetism in which a material is repelled by an external magnetic field)” is widely circulated, some researchers consider this statement ”seriously misleading”. A primary critique centers on the theorem’s assumption of only position-dependent interactions between charged particles, arguing that this is not a universal requirement of classical physics. Since Charles Galton Darwin’s work in 1920, it has been understood that the accurate description of magnetism arising from classical charged point particles necessitates the inclusion of velocity-dependent interactions within the Lagrangian. When this crucial assumption is relaxed, classical diamagnetism can indeed be derived. Recent experimental observations, such as perfect conductors exhibiting classical perfect diamagnetism (akin to the Meissner effect in superconductors (7)), appear to contradict the strict Bohr-Van Leeuwen conclusion (5). However, these phenomena can be consistently explained within the Darwin formalism, which accounts for velocity-dependent interactions and is applicable to dissipationless systems. Another significant nuance concerns the proof’s reliance on infinite limits in the phase space integrals. For systems with finite phase volume, a non-zero classical diamagnetic orbital moment can be derived. This suggests that the theorem’s strict zero-magnetization conclusion is an idealization applicable to infinitely extended classical systems.

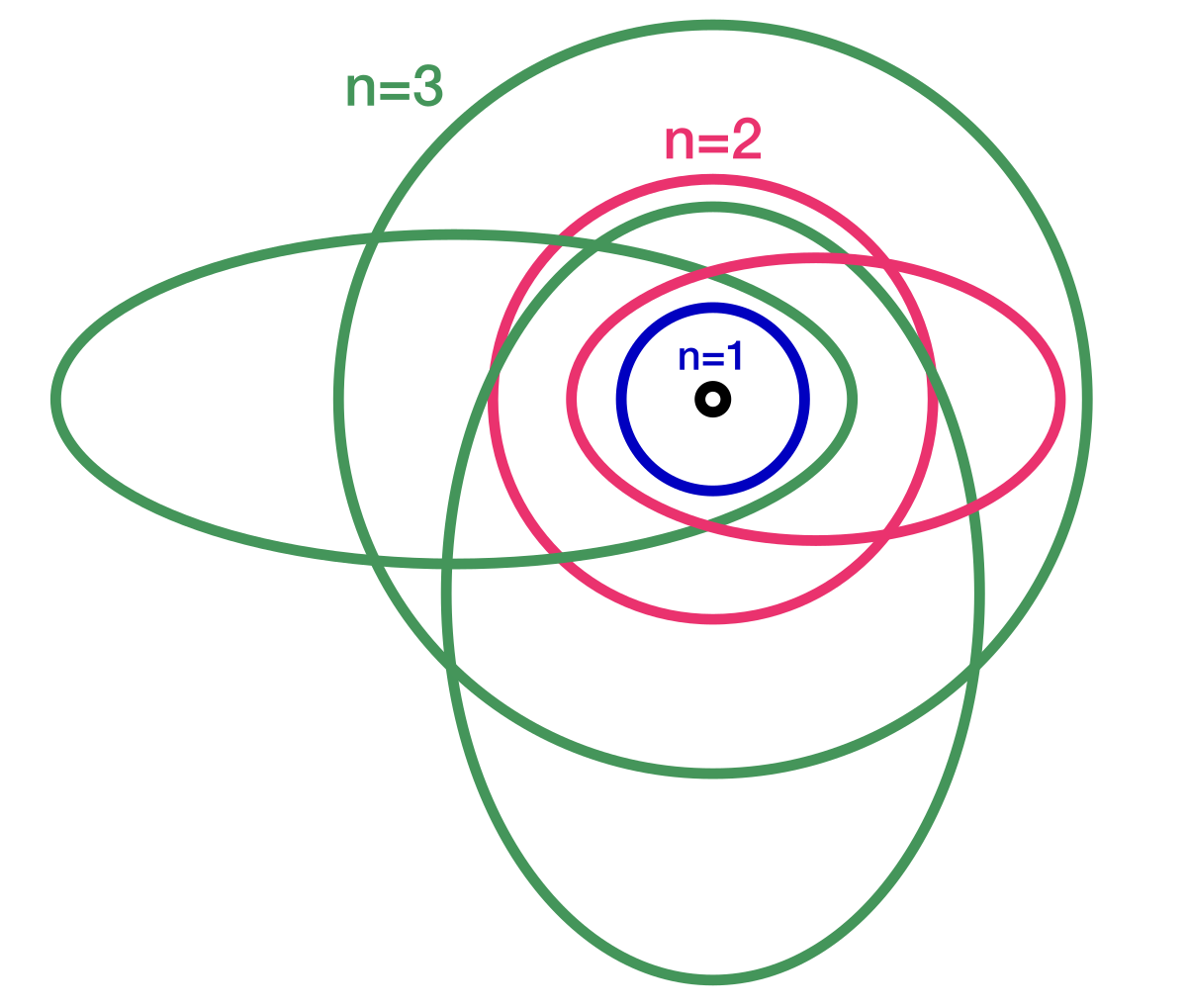

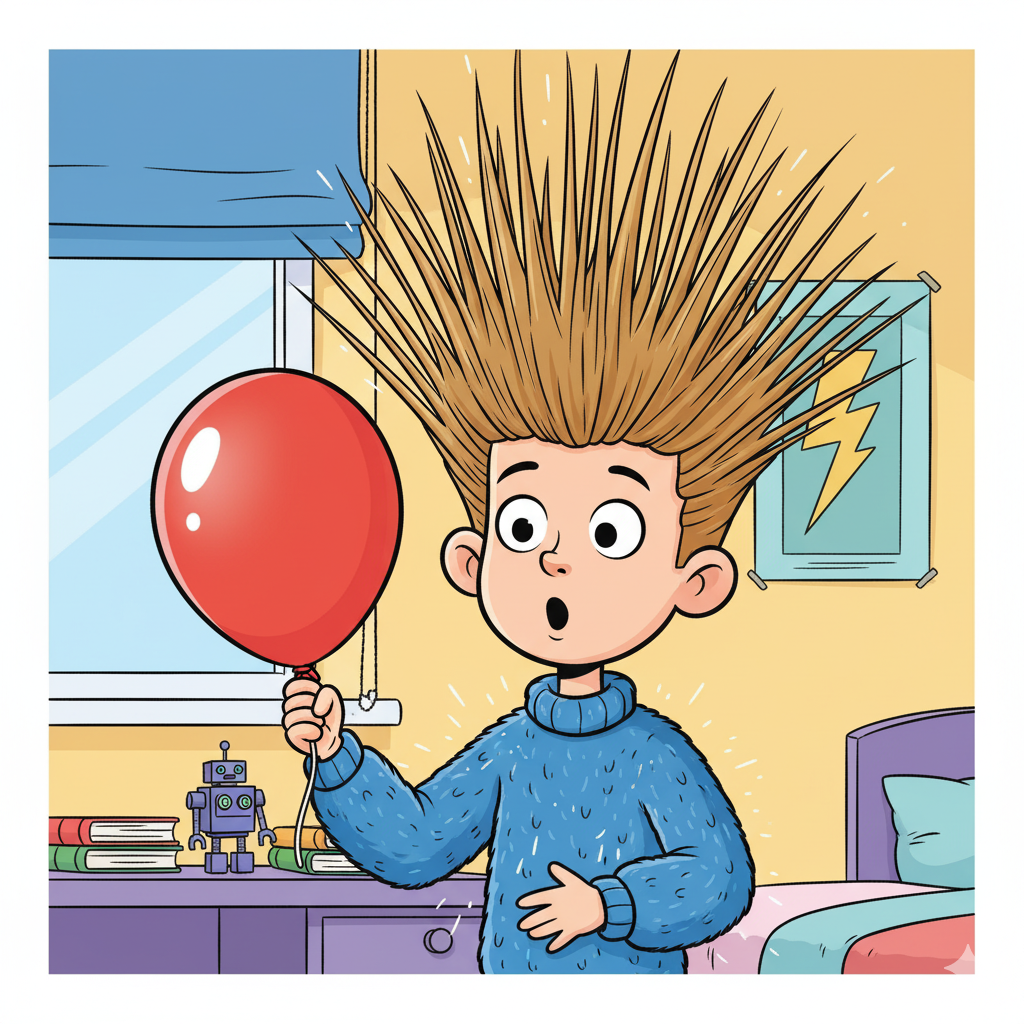

Just as the Bohr–van Leeuwen theorem demonstrates that classical physics cannot account for net magnetization in thermal equilibrium, it likewise fails to explain the persistent surface charges observed in triboelectric systems. Thus, the implications of the theorem extend beyond magnetism, revealing a deeper limitation of classical physics—its inability to describe stable charge separation. Although triboelectric charging is often classically attributed to electron transfer between materials with different electron affinities during contact or friction, the theorem underscores a broader principle: within classical statistical mechanics, equilibrium systems of charged particles cannot sustain either net charge separation or persistent current distributions. (13)

The key feature of triboelectricity is not only the transfer of charge but also the persistence of that charge on surfaces—charges remain localized for long periods instead of randomizing. According to classical theory, such stable charge separation should vanish, just as the Bohr–Van Leeuwen theorem predicts zero net magnetization in thermal equilibrium.

Fig.4.

This indirect connection of the Bohr-Van Leeuwen theorem to the classical inability to explain triboelectricity suggests that its implications are broader than just magnetic moments. It implies a more general classical failing: that classical statistical mechanics, when applied to microscopic charged systems in thermal equilibrium, cannot spontaneously generate or maintain any net macroscopic effect arising from ordered charge motion (magnetism) or stable charge separation/retention (triboelectricity). Both phenomena require non-random, stable configurations of charge that classical thermal equilibrium, by its nature, tends to randomize and dissipate. Therefore, the theorem is not solely about magnetism but underscores the fundamental inadequacy of classical equilibrium thermodynamics to explain any persistent, ordered microscopic electrical or magnetic phenomena without the explicit inclusion of quantum effects.

The Bohr-Van Leeuwen theorem finds significant utility in plasma physics (6), particularly in understanding diamagnetism within plasma elements (10). Discussions of the theorem in this context often reference Niels Bohr’s classical model of a gas of charged particles enclosed within a perfectly reflecting container. In this model, the walls reflect particles elastically, ensuring that every orbital current induced by the magnetic field is exactly balanced by an opposing current upon reflection. This symmetry leads to complete cancellation of net magnetization from the interior of the plasma element, resulting in zero net diamagnetism under equilibrium conditions. However, it is crucial to distinguish that diamagnetism of a purely classical nature can indeed occur in plasmas, but this is typically a consequence of thermal disequilibrium, such as a gradient in plasma density (9). This highlights a key boundary condition for the theorem, as it strictly applies to systems in thermal equilibrium. In classical kinetic equilibrium, the theorem implies that diamagnetic currents within the interior of a plasma element are identically zero.

The Bohr-Van Leeuwen theorem’s ”no-go” conclusion for classical magnetism profoundly impacted the trajectory of physics, propelling the development and widespread acceptance of quantum theory. This doesn’t just state a limitation; it effectively functions as a ”proof by contradiction” . If the established, well-tested framework rigorously leads to a result that contradicts observation (zero magnetization), then a new, fundamentally different framework must be required to explain the observed phenomena. Classical theories also couldn’t account for why blackbodies didn’t radiate infinite energy (the ultraviolet catastrophe), why light could eject electrons only above a certain frequency (the photoelectric effect), or why atoms emitted light at discrete wavelengths instead of continuous spectra. Models like Bohr’s quantized orbits and Sommerfeld’s refinements hinted that energy and motion inside atoms were not continuous but quantized. As more puzzles appeared — from atomic stability to specific heats and magnetism — scientists realized that a completely new framework was needed, leading to the birth of quantum mechanics: a theory where nature operates not in smooth curves, but in tiny, indivisible steps.