Insight Digest | Issue #7

In Insight Digest, we showcase the latest happenings in science research.Superconductivity in a 5' twisted bilayer WSe2

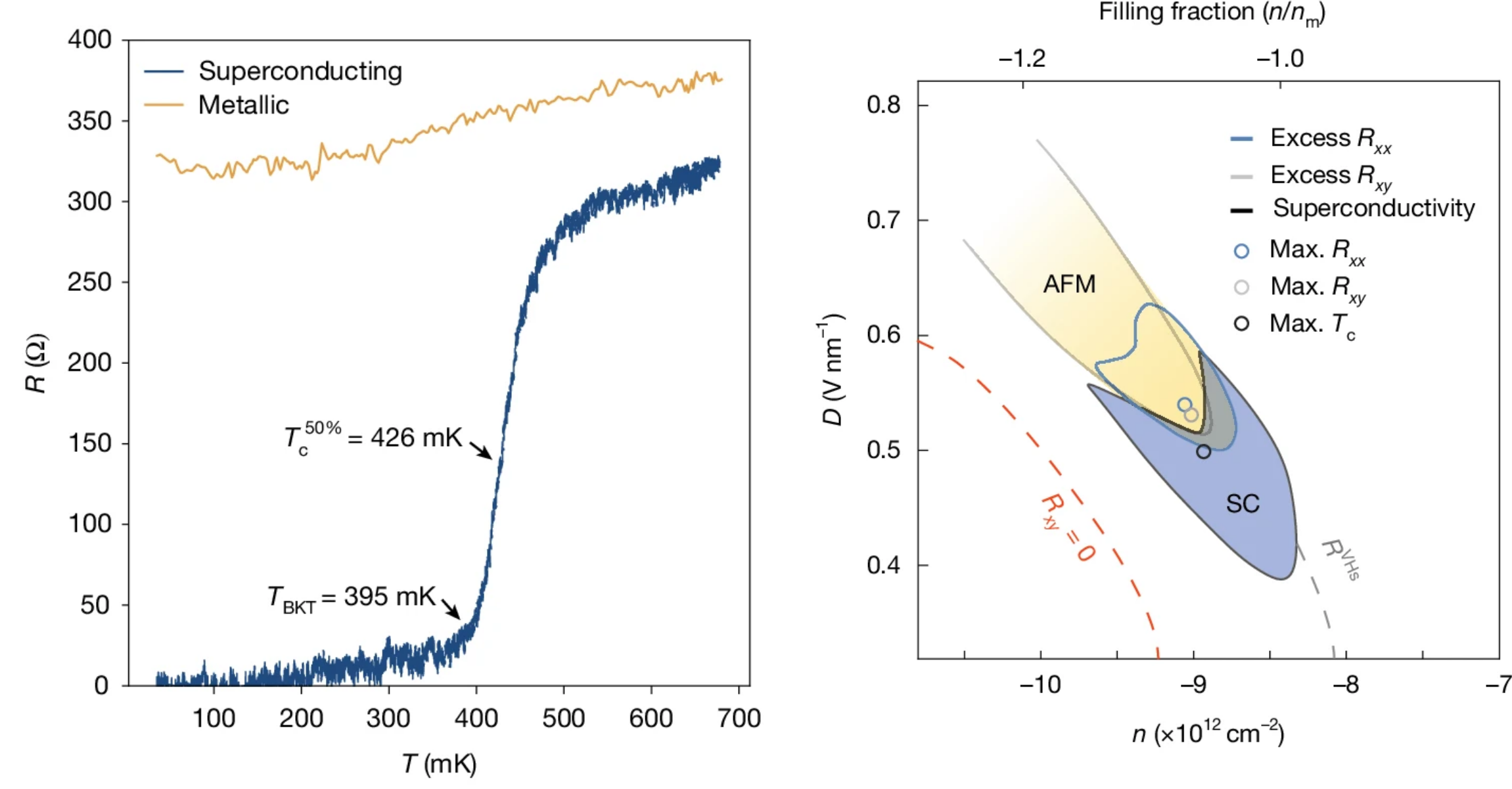

Guo, Y., Pack, J., Swann, J. et al. Superconductivity in 5.0° twisted bilayer WSe2. Nature 637, 839–845 (2025) (Department of Physical Sciences, IISER Kolkata) Keywords: Twisted bilayer graphene, superconductivity, strong-correlationsTwisted bilayer graphene is a paradigmatic platform in the regime of the strongly correlated system, and "twisted" here refers to the slight rotation between the layers of graphene(~1.1') , known as the magic angle, which creates a unique electronic structure with 'flat bands'. The flat band suppresses the kinetic energy relative to the coulomb enabling rich phases like magnetic ordering, unconventional superconductivity, and Chern ferromagnets , and associated quantum anomalous Hall states which appears depends sensitively on carrier density, displacement field, twist-angle homogeneity, and substrate alignment. A closely related material is twisted bilayer tungsten diselenide (tWSe\(_2\)),formed from two monolayers of the transition-metal dichalcogenide (TMD) but it also brings crucial new ingredients: strong spin-orbit coupling, robust spin-valley locking. These features reshape the effective low-energy models (often mapped to extended Hubbard models with valley degrees of freedom) and provide powerful electric-field control of bandwidth, band topology, and valley polarization. Experimentally, unconventional superconductivity has been reported in tWSe\(_2\) at a 5-degree twist with applying an external electric field.

At small twist angles, the two layers hybridize strongly and generate bands whose bandwidth can be comparable to the on-site interaction U , placing the system in an intermediate-coupling regime. In this window, neither a weak-coupling metal nor a fully Mott-localized insulator is guaranteed ; modest changes in control parameters can tip the balance. A perpendicular displacement field is especially powerful, distorts the bands, shifts van Hove singularities (critical points in the electronic band structure where the slope of the energy dispersion is zero) . Transport reflects this tunability ,without the twist the resistivity is metallic across dopings and displacement fields--decreasing with temperature and showing no sign of a gap. As the twist angle brings the system into the flat-band regime and the displacement field is tuned, the normal state can evolve from a conventional metal to a correlated metal with enhanced scattering . Upon approaching optimal fillings--where the density of states is elevated and screening is reduced--the system enters a superconducting phase, typically forming a dome in the displacement-field-density plane. On the flanks of this dome , indicating that pairing emerges in close proximity to other interaction-driven orders.In flat-band graphene systems, people have proposed that ordinary phonon-mediated pairing could produce superconductivity, and similar ideas exist for tWSe\(_2\) . This close tie between superconductivity and magnetism points instead to a magnetically mediated pairing mechanism, e.g. via spin fluctuations, rather than conventional phonons.

The study offers a fresh perspective on the interplay between magnetic ordering and superconductivity that goes beyond the scope of standard transport measurements. It also provides a useful comparison with known graphene and TMD systems, highlighting the crucial role played by twist angle in shaping these correlated phases.

The Microbe That Blurs the Boundary of Life

Ryo Harada, Yuki Nishimura, Mami Nomura, Akinori Yabuki, Kogiku Shiba, Kazuo Inaba, Yuji Inagaki, Takuro Nakayama. bioRxiv 2025.05.02.651781 (Department of Biological Sciences) Keywords: Archaea, Minimal genome, Symbiosis, Origin of life, Viral-cellular boundaryFor more than a century, biology has maintained a sharp distinction between viruses and cells. Cells grow, divide, and metabolize independently; viruses remain inert until they hijack a host cell. But a discovery by Harada et al., reported in their seminal paper, has challenged this comfortable binary. They identified Candidatus Sukunaarchaeum mirabile--a novel archaeon so extraordinarily reduced in its genetic material that it exists in a conceptual twilight zone between living cells and viral parasites.

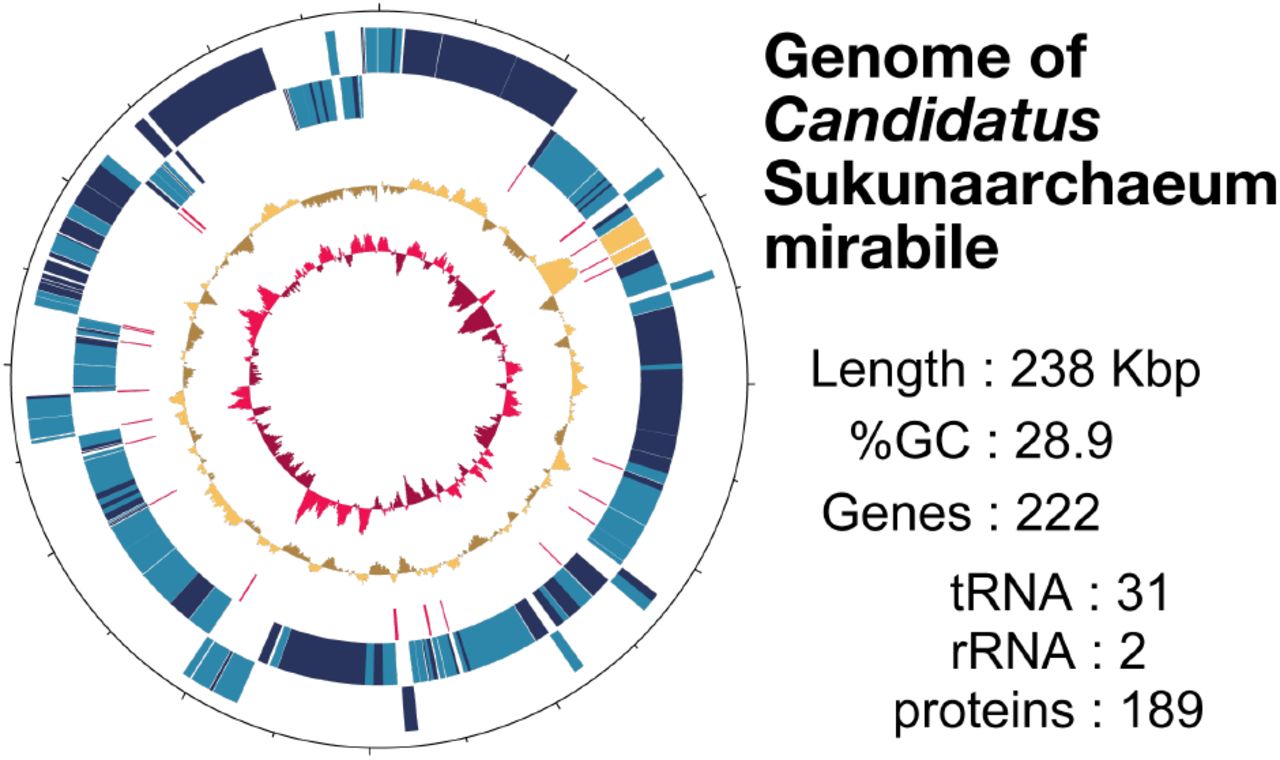

The discovery began almost by accident. Researchers at the University of Tsukuba in Japan were sequencing the complete genomic contents of a dinoflagellate--a marine plankton organism called Citharistes regius--which was already known to harbor symbiotic cyanobacteria. Among the expected genetic sequences, they found something entirely unexpected: a small, circular loop of DNA only 238,000 base pairs long. This was remarkable because the previous record for the smallest known archaeal genome stood at 490,000 base pairs. The newly discovered genome was less than half that size, yet phylogenetic analyses confirmed that it belonged to a cell--an archaeon--not a virus. The organism bearing this genome was named after Sukuna-biko-na, a small-statured deity in Japanese mythology, embodying both its diminutive scale and its position between two worlds: Candidatus Sukunaarchaeum mirabile (mirabile meaning "remarkable" in Latin).

What makes Sukunaarchaeum so extraordinary is not merely the size of its genome, but what that genome contains--and more tellingly, what it lacks. The 238 kilobase genome encodes a profoundly stripped-down, replicative core consisting of the machinery necessary for DNA replication, transcription, and translation. It contains approximately 189 protein-coding genes, nearly all dedicated to self-propagation. However, it lacks virtually all recognizable metabolic pathways. The archaeon cannot synthesize the amino acids that build proteins, cannot produce the nucleotides that build DNA, and cannot generate its own energy. This extreme reduction places it in an unprecedented position: it is a cell in structure yet functions like a parasite, outsourcing nearly every biological process except replication to its host, the dinoflagellate Citharistes regius. In this sense, it resembles a virus more than any previously known cellular organism--yet it retains the ribosomal machinery and genetic architecture of true cellular life.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond taxonomy. The genome organization of Sukunaarchaeum offers a rare window into fundamental questions about the nature of life itself. What are the minimal genetic requirements for an entity to be considered "alive"? Is cellular life defined by metabolic autonomy, or can an organism retain that designation by virtue of possessing its own replication machinery? Harada and colleagues argue that Sukunaarchaeum challenges conventional functional distinctions between minimal cellular life and viruses, suggesting that the boundary between these categories may not be as absolute as traditionally conceived.

From an evolutionary perspective, Sukunaarchaeum may represent a living snapshot of an ancient transition. Many evolutionary biologists propose that early life originated from simple, highly dependent molecular systems--perhaps RNA-based replicators that gradually acquired metabolic sophistication and independence. The authors suggest that Sukunaarchaeum could be a remnant of such an intermediate state, a surviving "evolutionary intermediate" that has managed to persist within symbiotic relationships over billions of years. If this interpretation is correct, the archaeon offers unprecedented empirical evidence for a gradualist model of life''s emergence from non-living chemistry.

Furthermore, environmental sequence data analyzed by the research team revealed that this is not an isolated curiosity. For researchers working on synthetic biology and the design of minimal cells, Sukunaarchaeum offers both inspiration and caution. It demonstrates that a cell can function with far fewer genes than previously thought possible, yet raises the question of what trade-offs accompany such reduction.

Finding the Right Balance for more Stable Qubits

Bassi, M., Rodríguez-Mena, E.A., Brun, B. et al. Optimal operation of hole spin qubits. Nat. Phys. (2025) (Department of Physical Sciences) Keywords: Magnetic-field control, Hole spin qubits, Semiconductor quantum devicesQuantum computers are often discussed as futuristic machines, but their development depends on solving practical problems at extremely small scales. One such challenge is how to operate qubits--the basic units of quantum information--in a way that is both fast and stable. A recent paper published in Nature Physics addresses this issue for a promising type of qubit known as a hole spin qubit, offering new insight into how these systems can be controlled more reliably.

The work was carried out by researchers at Université Grenoble Alpes, CEA-IRIG (France), and collaborating institutions, led by Silvano De Franceschi and Vivien Schmitt. Their study focuses on semiconductor-based qubits, particularly those built using silicon. This is significant because silicon qubits can, in principle, be fabricated using existing industrial techniques, making them attractive for scalable quantum computing.

Unlike electron-based qubits, hole spin qubits rely on "holes," which are the absence of electrons in a material. These holes possess a quantum property called spin that can store information. Hole spins respond strongly to electric fields, allowing for fast electrical control. However, this same sensitivity also makes them vulnerable to electrical noise, which can disturb quantum states and reduce qubit performance.

To address this, the researchers explored how the qubits behave under different operating conditions. By carefully changing the orientation of an external magnetic field, they identified specific regions, referred to as "sweet lines," where the qubits become much less sensitive to charge noise. At these operating points, stability improves while efficient electrical control is preserved, striking an essential balance for quantum operations.

An important result of the study is that these optimal conditions are not fixed. By adjusting voltages on nearby electrodes, the position of the sweet lines can be shifted, allowing multiple qubits to be tuned into low-noise regimes at the same time. This tunability is crucial for building larger quantum processors, where many qubits must operate together in a controlled and reliable manner.

The research builds on years of experimental and theoretical work in semiconductor quantum systems and combines advanced nanofabrication, modeling, and measurements performed at extremely low temperatures. Key contributors include Marion Bassi, Esteban-Alonso Rodríguez-Mena, Boris Brun, Simon Zihlmann, and others, reflecting the collaborative nature of modern physics research.

While this study does not present a complete quantum computer, it resolves an important operational challenge and provides clear guidance for how hole spin qubits can be used effectively. Incremental advances like this play a central role in turning quantum computing into a scalable and practical technology.

When a Cyclone Shakes the Sky: How Super Cyclone Amphan Disturbed Earth''s Upper Atmosphere

O. M. Patil, D. Kar, N. Parihar, R. Singh, and A. P. Dimri, Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics, vol. 277, p. 106654, Oct. 2025 (don;t give please) Keywords: Super Cyclone Amphan, Atmosphere-Ionosphere Coupling, Cloud-to-Cloud Lightning, Atmospheric Gravity Waves, Upper Atmospheric Disturbances, Bay of BengalTropical cyclones are usually studied for the destruction they cause at Earth''s surface--strong winds, heavy rainfall, storm surges, and flooding. This study shows that their influence does not stop there. Using Super Cyclone Amphan (May 2020) over the Bay of Bengal as a case study, we demonstrate that intense tropical cyclones can also disturb the upper layers of Earth''s atmosphere, including regions that host satellites and radio communication systems.

The most interesting finding of this work is the clear, multi-altitude link between intense cyclone-driven convection, lightning activity, atmospheric gravity waves, and disturbances in the lower ionosphere. By combining observations from several satellites, we show that Amphan''s powerful convective clouds and strong lightning activity generated atmospheric gravity waves--ripples in the atmosphere similar to waves produced when a stone is thrown into water. These waves traveled upward from the lower atmosphere through the stratosphere and mesosphere, reaching the lower thermosphere and ionosphere.

A particularly novel aspect of this study is its detailed focus on cloud-to-cloud (CC) lightning, which has been largely overlooked in cyclone studies over the Indian region. We find that CC lightning intensified during Amphan''s rapid strengthening phase, especially within the eyewall region, and that a large fraction of these flashes were high-energy and positively charged. This lightning behaviour closely followed the cyclone''s intensification and weakening, suggesting that CC lightning can serve as a valuable indicator of strong internal storm dynamics.

Why does this matter? For the space-weather and ionospheric community, this study strengthens the evidence that weather systems near Earth''s surface can directly affect the near-space environment through gravity waves. Such disturbances can influence radio wave propagation, satellite drag, and navigation systems like GPS. For meteorologists and climate scientists, the results highlight lightning and gravity waves as key but under-represented components of cyclone dynamics, offering new pathways to improve storm monitoring and modelling.

More broadly, this work enriches Earth system science by demonstrating how tightly connected different atmospheric layers are--from the ocean-driven cyclone at the surface to electrical and wave processes over 100 km above Earth. By bridging meteorology, atmospheric electricity, and space physics, this study helps move us closer to a truly integrated understanding of how extreme weather events impact the entire Earth-atmosphere-space system.