The World of Diophantus

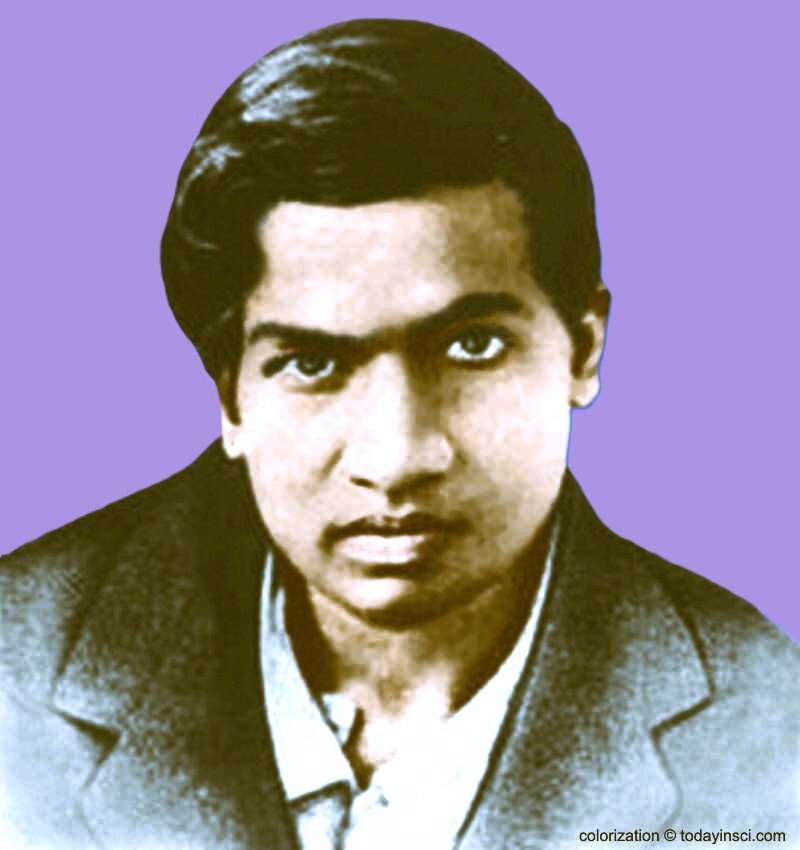

No excuse is needed to celebrate mathematics, but there are two special days selected by the community. The National Mathematics Day is celebrated in India on Ramanujan’s birthday, the 22nd of December but I defer the celebration of this to another time. The other one is Pi day, the 14th of March, which has been selected and universally accepted as the International Mathematics Day (there is actually a building in Hong Kong which is shaped like π). Regarding this choice of π-day, I would say:

We had this year’s Pi Day

nine months back on a Friday.

To Pi, 22 by 7 is closer

but somehow 3.14 is kosher.

But who cares? Let’s celebrate anyway!

Diophantus of Alexandria

Metrodorus indicated the life span of Diophantus through a puzzle poetically as:

’Here lies Diophantus,’ the wonder behold.

Through art algebraic, the stone tells how old:

’God gave him his boyhood one-sixth of his life,

One twelfth more as youth while whiskers grew rife;

And then yet one-seventh ere marriage begun;

In five years there came a bouncing new son.

Alas, the dear child of master and sage

after attaining half the measure of his father’s life chill fate took him.

After consoling his fate by the science of numbers for four years, he ended his life.’

This puzzle implies that Diophantus’s age x =?? is a solution of the equation:

For those who wish to verify the answer they got, here is a crossword type of hint: endless Hindustani Classical flautist!

Diophantus was interested in solving polynomial equations in many variables where he sought solutions in integers or, more generally, in rational numbers. He wrote a number of books titled ‘Arithmetica’ many of which have got lost. Thus, the nomenclature of Diophantine equations arose to describe the broad subject of finding integer solutions of polynomial equations. For instance, the Diophantine equation seeks integer triples (the so-called Pythagorean triples) describing the lengths of the sides of a right-angles triangle.

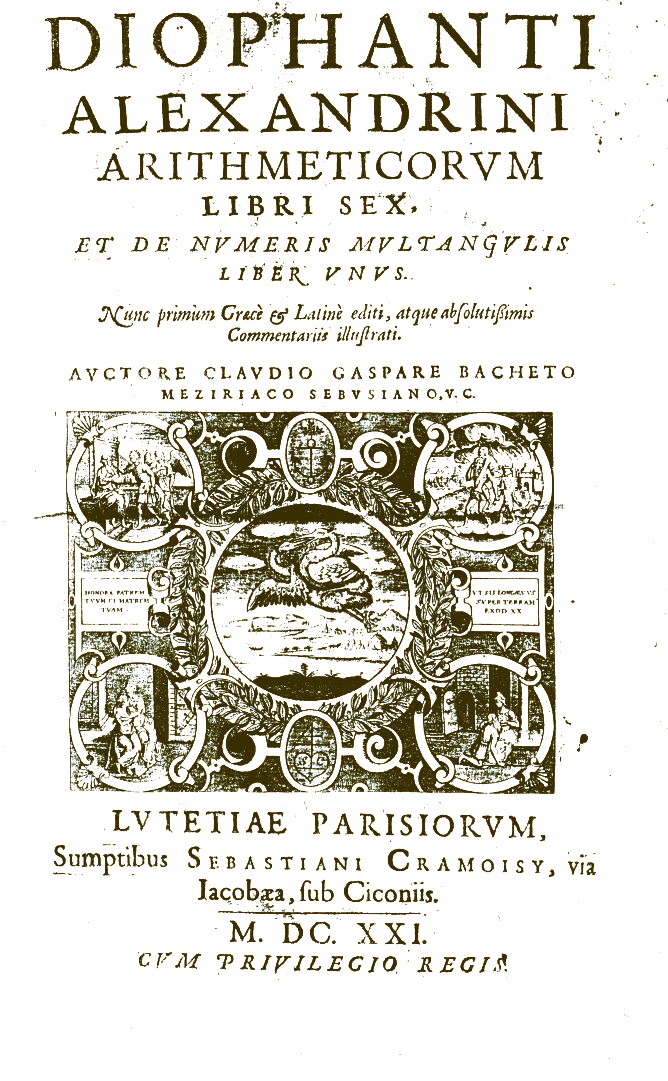

The amateur mathematician Pierre de Fermat had, in his copy of Bachet’s translation of Diophantus’s Arithmetica, made a famous marginal note which came to be known as Fermat’s last theorem and which is now a theorem. It says that for any n > 2 there are no solutions of the equation in non-zero integers x, y, z; see the departure from the case when we get infinitely many Pythagorean triples.

In regard to the history of Fermat’s last theorem, many famous mathematicians like Cauchy had unsuccessfully attempted (and thought to have solved) it. The first seriously successful attempt was by Kummer when he proved Fermat’s assertion for certain types of primes called regular primes. Sophie Germain (who had to go under an alias of a male name as women were not allowed to enrol at the university at that time) was a protege of Gauss and she proved the truth of Fermat’s assertion when the exponent is a prime p such that is also a prime. Only in the 1980s, the whole picture changed with the advent of highly state-of-the-art methods into this topic by Gerd Faltings, Gerhard Frey, Kenneth Ribet and finally ending with the deep work of Andrew Wiles supported by Richard Taylor. One might say:

Solved first by the great Cauchy.

What a mistake made - Gosh, he!

Then it was Kummer’s time.

He did every regular prime.

Germain came and shouted ‘Whoopee!

Done, if we know about 1 + 2p’.

The uproar after Faltings, Gerd

went ‘Mordell’s done; spread the good word!’

We know who then jumped into the fray

whose elliptic curve could exist no way!

Ribet said ‘Taniyama does

put a stop to all this fuss!’

And then Wiles was heard telling Taylor

now’s the time; let’s go and nail her!’

We conclude from this saga of Fermat

the importance, above all, of Karma!

The problem of finding integer solutions of polynomial equations is so basic and ubiquitous that it is not surprising Diophantine equations arise in diverse situations from the most abstract to the very concrete. In the following article, we take a peek into many Diophantine equations that arise in mathematics ranging from the recreational kind of questions to those that are more fundamental and deeper.

Sums of Powers

Fermat had conjectured that every positive integer is a sum of four squares of integers. Later in 1770, Waring conjectured that every positive integer N is a sum of at the most 9 cubes of positive integers. This was proved by Wieferich (1909) - with a correction carried out by Kempner (1912). In fact, if N is large enough, 7 cubes suffice (Linnik 1942); can 7 be reduced to 6 or 5 or 4? The answer is still unknown.

If we allow cubes of negative integers also, then 5 cubes suffice but, it is again unknown if 4 cubes suffice. Therefore, the problem as to which integers are sums of three integer cubes becomes very interesting.

Regarding this last question, by 2021, the only two elusive cases of 33 and 42 remained among the numbers up to 100. This was finally settled by Andrew Booker from Bristol, and Andrew Sutherland from MIT - authorities on parallel computations. They used ‘Charity Engine’, a world-wide computer that harnessed idle, unused computing power from over 500000 home PCs to create a crowd-sourced platform.

The most difficult case of 42 resolved using a computing platform reminiscent of ‘Deep Thought’, the giant machine which gave the answer 42 in Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. For those who have not had the pleasure of reading this work, we recall from it: The Earth was actually a giant supercomputer, created by another supercomputer, Deep Thought. ‘Deep Thought’ built by its creators to give the answer to the “Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything”. After eons of calculations, the answer was given simply as “42”. Deep Thought was then instructed to design the Earth supercomputer to determine what the Question actually is!

For the sake of those who are interested, here is the solution expressing 42:

In passing, we mention that it is easy to see the smallest solutions to expressing 3 as a sum of three cubes of integers are:

For those who wonder how big the next solution could be, here it is:

Concerning such questions, Terence Tao suggests as a challenge for the clairvoyant:

It occurs to me that these sorts of questions would be excellent challenge questions to pose to any psychics who claim to be in contact with superintelligent aliens, since the solutions are already expected to be produced by computer search in a few years but would be instantly verifiable evidence of some extraordinary computational or intellectual resource if produced sooner.

The Fab cab

Everyone must have heard of the famous taxicab number 1729 and Ramanujan’s story thanks to Mahalanobis, who was a contemporary of Ramanujan at Cambridge (and who actually taught him for the first time how to get inside an English bed after realizing that for months Ramanujan had been freezing without being privy to this know-how). The Ramanujan taxicab number concerns the Diophantine equation . When Hardy mentioned that the taxicab he travelled bore the number 1729 and this number appeared dull to Hardy, Ramanujan immediately responded that this was far from a dull number as it was the smallest positive integer which is a sum of two cubes of integers in two different ways. The two integer solutions (12, 1) and (10, 9) are the only ones which is easy to prove, but a nice exercise it to check that each number < 1729 has at the most one expression as a sum of two cubes.

However, in this context, what may not be well-known is that has infinitely many rational solutions. For instance, if u, v is a solution, then so is and .

Enter Sylvester

As alluded to earlier, Diophantine equations are polynomial equations for which one seeks integer or rational solutions. Existence of rational solutions is often an easier problem to study than that of determining if integer solutions exist. A heuristic reason is that the set of rational solutions may have a much better structure - for instance it often has the structure of a group where two rational points can be composed to give a new third rational point. For example, a Diophantine equation like has only two integer solutions (x, y) = (3, 9), (3,−9) whereas if we consider a picture of the real locus of this equation, one may produce a new point with rational co-ordinates from two points with rational co-ordinates simply by drawing a chord between the two points and then reflecting about the x-axis the third point where this chord intersects the graph. To start with one can draw the tangent at (3, 9) and take the point where it cuts the graph and reflecting that point. In this manner, we can produce infinitely many solutions with rational co-ordinates! Of course, an equations like with a cubic polynomial with distinct roots are special; they are called ‘elliptic curves’ and they have a group law as described above where two points give rise to a third point.

Many classical problems lead to Diophantine equations which involve elliptic curves. One such is a problem due to Sylvester. Determining which integers n are sums of TWO rational cubes, has a rich history tracing back to Sylvester who predicted that prime numbers p which leave a remainder 2 or 5 when divided by 9 are not sums of two rational cubes, while primes which leave a remainder of 4, 7, or 8 are sums of two rational cubes. In contrast, primes p that leave a remainder of 1 or 8 when divided by 9 may or may not be sums of two rational cubes. The problem gets related to the elliptic curve . Only very recently the last prediction mentioned above (considered particularly difficult) has been proved for infinitely many prime numbers.

In passing, we mention an amusing anecdote involving Sylvester. While teaching in the United States, he had an encounter with an unruly student and believed that the student had been fatally wounded by Sylvester during a skirmish. Sylvester returned to England still under the mistaken impression that he had killed a student! While in England, he had tutored many people in mathematics and statistics, one of whom was Florence Nightingale. Sylvester was also responsible for introducing several interesting names in mathematics - like syzygy.

Not as easy as Pi

Like the Diophantine equations, a related notion that arises in many situations is that of Diophantine approximation - we briefly mention one place where π occurs. Here is a routine-looking question? Is the infinite series convergent?

The convergence of the series depends on the behavior of the sequence as gets infinitely large and, this behavior is mysterious. It depends on how well can be approximated by rational numbers - something unknown as yet! To make it a bit more precise, we briefly describe something called the irrationality measure of an irrational number α.Consider the positive numbers a > 0 for which the distance of from a rational number can be less than the quantity only for finitely many . The smallest (or the infimum of) all such is defined to be the irrationality measure of . It quantifies how well-approximable the number is by rational numbers.

The Dirichlet box principle implies that the irrationality measure and generically (that is, almost all) have . For a specific number, it is difficult to find ; for instance, but, the constant is still unknown! One knows but not much more is known Here is the shocker - the series diverges if and converges if, . So, take your pick! Before we move on to other things, we recall an interesting mnemonic to remember the first few digits of :

“Now I want a drink, alcoholic of course, after the heavy lectures involving quantum mechanics!”

Hilbert’s 10th problem

We already mentioned that many problems of mathematics can be formulated as seeking solutions of certain Diophantine equations. However, this statement goes much further. In a sense of formal mathematical logic, every mathematical problem can be so formulated! This is formally the so-called Hilbert’s 10th problem - one of the 23 problems posed by david Hilbert during the 1900 International Congress of Mathematicians to lead the way for mathematics in the next several years.

Hilbert’s famous 10th problem asserted: “Given a diophantine equation with any number of unknown quantities and with rational integral numerical coefficients: To devise a process according to which it can be determined by a finite number of operations whether the equation is solvable in rational integers.”

As it turned out, the answer was obtained in 1970 and unfortunately, it turned out to be negative. More precisely, the resolution due to Martin Davis, Putnam, Julia Robinson and Yuri Matiyasevich proves that there is no general algorithm that, given any Diophantine equation, decides whether it has solutions in positive integers or not. In more technical terms, the notions of ‘effectively enumerable’ sets and ‘Diophantine’ sets coincide.

The ideas appearing in the resolution of the 10th problem yield interesting implications such as:

“There exists a polynomial in 26 variables for which the set of positive values when the variables take positive integer values, equals the set of prime numbers!” One can write the polynomial down explicitly using the symbols a to z for the 26 variables.

Pell-Mell

We discuss a type of equation that arises in many contexts and we start with an elementary problem that leads to it.

Think of a fruit-seller arranging her fruits in a triangular pattern in the morning and in a square pattern in the evening. Can she do both of these with the same number of fruits? For instance, if he has 36 fruits, he can do this because . Which other squares are so expressible as ‘triangular numbers’?

If , then . Thus, is a solution of the equation . Being aestheticallyminded fruit-sellers, all of us of course want to know what the solutions of are! Before addressing how to solve this equation, we jump to another instance when the same equation arises and it involves Ramanujan.

In the Strand magazine, Mahalanobis had seen the following problem which he mentioned to Ramanujan: Imagine that you are on a street with houses marked 1 through n. There is a house in between such that the sum of the house numbers to the left of it equals the sum of the house numbers to its right. If n is between 50 and 500, what are n and the house number? Ramanujan thought for a moment and replied “Take down the solution” and dictated something called a ‘continued fraction’ (to be explained below) saying that it contained the solution! Evidently, Ramanujan wanted to have some fun instead of directly giving the answer! So, what is behind this?

If the house number is , then we have The LHS is and if we add to both sides, we have . Multiplying by 8 and adding 1, we have , the very same equation encountered by the fruit-seller! One can similarly look at for any square-free positive integer d.These equations are popularly (and erroneously!) known as Pell equations. Interestingly, it turns out that there are infinitely many pairs m, n of positive integer solutions of and essentially, they are all generated froma single pair. The ancient Indian mathematicians (especially Brahmagupta,Bhaskara II and Jayadeva) studied the equations and solved them. What is more - they gave an algorithm (the so-called Chakravala or cyclic method) which produces all the solutions.

In 1657, Fermat, writing to his friend Frenicle, he posed “to the English mathematicians and all others” the problem of finding a solution of “pour ne vous donner pas trop de peine” like N = 61, 109.

The 20th century great Andr´e Weil’s comment on this was: “What would have been Fermat’s astonishment if some missionary, just back from India, had told him that his problem had been successfully tackled there by native mathematicians almost six centuries earlier ?”

Indeed, in 1150 A.D., Bhaskara II gave the explicit solutions

Indeed, Brahmagupta (598-665) had already solved this equation in 628 A.D. for several values like N = 83 and N = 92.

Brahmagupta had remarked, “Kurvannaavatsaraad ganakah” - meaning (approximately), “a person who is able to solve these within a year is truly a mathematician”’ !

The wrong attribution to Pell of these equations is due to the most prolific of mathematicians - Leonhard Euler, but the name has stuck. In view of the above understanding of mathematical history, now the equations are being increasingly referred to as the Brahmagupta-Pell equations. Perhaps the oldest Diophantine equation to be considered is one posed by Archimedes (287 -212 B.C.) to Eratosthenes known as the cattle problem. We avoid the long wording and just state the modern equivalent which is to find the smallest solution of the equation it turns out that the smallest solution has at least 206545 digits.

We make a brief interlude on continued fractions and indicate how they are used in solving the Brahmagupta-Pell equations.

A simple continued fraction (SCF) is a nested expression

where are integers and for all . That is, consider the sequence of fractions , where , where etc. The above infinitely nested expression stands for the limiting value of the fractions (which can be easily shown to exist). The main point is every real number can not only be expanded as a decimal but also expanded as a simple continued fraction by the ‘greedy’ algorithm: Consider any real number which is not already an integer. Then, take to be the greatest integer not exceeding . Next consider the real number

Take and consider etc. In this manner, we get a continued fraction expansion It is easy to see that this is eventually periodic if and only if is the root of a quadratic polynomial with rational coefficients. For any square-free positive integer N, the SCF of looks like .

For instance, using the greedy algorithm, let us find the SCF for the irrational number .

Thus, we have a repetition and

So, .

Here is the interesting thing about SCFs of and their relation to the Pell equation . , the rational numbers , etc. are called convergents of the SCF. When the SCF is periodic like that for , the penultimate convergent before the recurring period gives a solution of . This is so simple to prove that it is explained in the classical school level text by Hall and Knight. This is how Ramanujan could give the solution to the house number problem quickly.

For example,

gives the penultimate convergent before the period to be . Then, is a solution of

(as the period is of even length).

Note that has no solution as seen by looking at the

remainders on dividing by .

Another example is which has the penultimate convergent before the period to be .

Then is a solution of (as the period is of odd length). Think of this as the equality

From this a solution for can be obtained by considering . Then is a solution of .

Congruent Number Problem

This is one of the oldest problems in Diophantine equations. A natural number d is said to be a congruent number if there is a right-angled triangle with rational sides and area d. For example, 5, 6, 7 are congruent numbers. Of course, 6 is congruent as seen from the usual 3, 4, 5 triangle. To see that 5 is a congruent number, we consider the right-angled triangle with sides

. For , look at a right triangle with sides . How did we guess this? More importantly, how do we decide if a given number is a congruent number? This will be done by relating it to another problem! This is the following one.

Can we have an arithmetic progression of three terms which are all squares of rational numbers and the common difference d? That is, can be squares of rational numbers and x rational? The congruent number problem and the above question are equivalent!

Indeed, Let be the sides of a right triangle with rational sides. Then is such that form an arithmetic progression. Conversely, if are three rational squares in arithmetic progression, then: are the legs of a right angled triangle with rational legs, area and rational hypotenuse because .

Now are not congruent numbers. The fact that

are not congruent numbers is essentially equivalent to Fermat’s last

theorem for the exponent (!)

Here is the argument. If , for some

rational numbers then are rational

numbers satisfying . In terms of integers, this is the

Diophantine equation . As this has no non-zero

integer solutions, it follows that is not a congruent number.

Similarly, if for rational numbers

, then are rational numbers satisfying

. Again, the nonexistence of solutions shows that is

not congruent.

Here is a (rather unusual!) way of using the above fact that is not a congruent number to show that is irrational. Consider the right-angled triangle with legs and hypotenuse . If were rational, this triangle would exhibit as a congruent number! Though it is an ancient problem to determine which natural numbers are congruent, it is only in late 20th century that substantial results were obtained and progress has been made which is likely to lead to its complete solution. The rephrasing in terms of arithmetic progressions of squares emphasizes a connection of the problem with rational solutions of the equation ; recall we referred to such equations as “elliptic curves”. It is easy to show that: The positive integer is a congruent number if, and only if, the elliptic curve has a solution with .

In fact, implies is a rational solution of . Conversely, a rational solution of with gives the rational, right-angled triangle with sides and area .

In a nutshell, here is the reason we got this elliptic curve. The real solutions of the equation defines a surface in -space and so do the real solutions of . The intersection of these two surfaces is a curve whose equation in suitable co-ordinates is the above elliptic curve! The connection with elliptic curves has been used, more generally, to show that numbers which are or mod are not congruent. This uses much deeper mathematics. Further, assuming the truth of a famous, deep, open conjecture known as the , it has been shown that this is a complete characterization of congruent numbers.

Arithmetic Progressions

Here is a set of questions on arithmetic progressions of natural numbers which leads us to some very interesting Diophantine equations. Can we have a finite arithmetic progression such that a first part has the same sum as that of the second part Note More generally, we can try to break an arithmetic progression into THREE parts with equal sums; here, we mean that each of the three parts consist of consecutive terms. The answer turns out to be ‘No’ which we leave as an exercise for the interested reader.

A related question is whether we can have four perfect squares of positive integers in arithmetic progression. Well, if are in arithmetic progression, then Then would be 3 parts of an A.P. whose sums are all equal, which we mentioned above does not exist. Hence, we cannot have four perfect squares of positive integers in an arithmetic progression.

Erdös-Selfridge, Catalan

The fact that a product of (at least ) consecutive positive integers can not be a perfect power was settled more than 50 years back by Erdös & Selfridge. In other words, the Diophantine equation does not solutions in positive integers .

Erdös-Selfridge theorem is so simple to state (and easy to prove for 2 or 3 consecutive numbers) that one may be tempted to think it could perhaps have an elementary proof. However, for , the proof needs deeper properties of prime numbers, such as a classical theorem due to Sylvester which asserts that any set of consecutive numbers with the smallest one contains a multiple of a prime . The special case of this when the numbers are is known as Bertrand’s postulate.

Yet another Diophantine equation arises from the natural question: Which natural numbers have all their digits to be 1 with respect to two different bases?

Equivalently, if the bases are and the numbers have and

digits respectively, then we wish to solve

in natural numbers .

For example and have this property;

This was observed by Goormaghtigh nearly a century ago. However, it

is still unknown whether there are only finitely many solutions in

. In fact, no other solutions are known. For any , it was proved only as recently as in 2002 that

the number of solutions for is at the most .

Another question is whether one can have different finite arithmetic progressions with the same product. For instance for all natural numbers . So, the question as to whether there are other solutions to the Diophantine equation where are positive rational numbers and if is quite open. It is only in 1999 that using deeper ideas from the subject of , it was proved that if are fixed, then the equation has only finitely many solutions in integers apart from some exceptions which occur when . A deep unsolved conjecture due to Erdös in 1975 asserts:

For each , the number of satisfying with min, is finite.

There are so-called transcendental methods that often prove by general ideas that certain classes of Diophantine equations can have only finitely many integer solutions. But, they are not ‘effective’ in the sense that one does not know any number which bounds the size of possible solutions. For instance, for the so-called Catalan equation , Robert Tijdeman proved (ineffectively) finiteness of the number of solutions. Later, although it was made effective by Langevin, he obtained an upper bound for that was of the order of which is out of the range of any present-day computer. Of course, later in 2024, the Catalan equation was completely solved by Preda Mihailescu by totally different methods; he showed that the only perfect powers differing by are and . A more general conjecture due to S S Pillai is still open; it asserts that the gaps in the sequence of perfect powers tends to infinity.

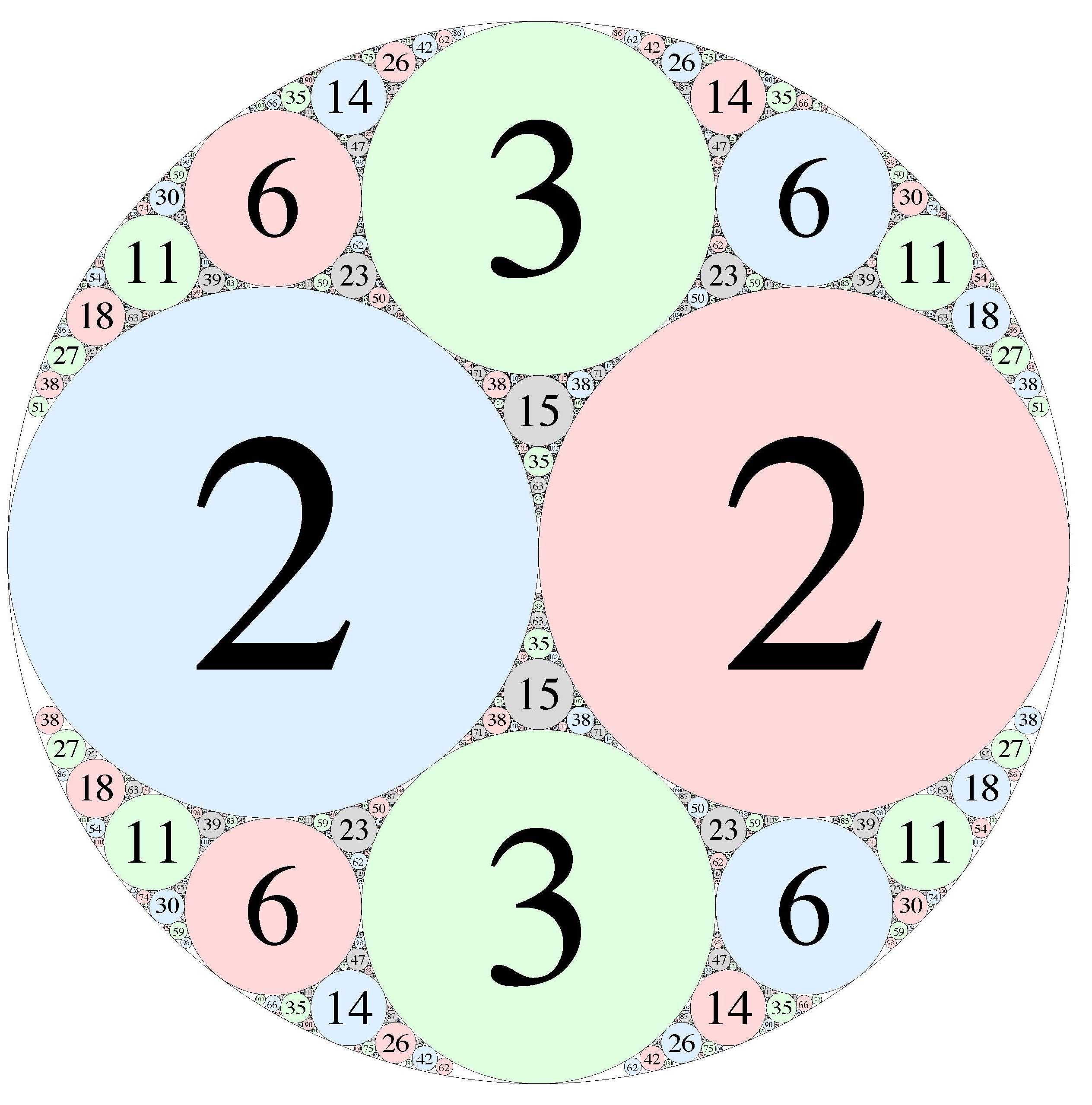

Apollonian circle packing.

Apollonius from 200 BC discovered something beautiful. If we have three circles touching each other, one may place another circle touching all three.

In the 17th century, Descartes discovered the remarkable fact that the four curvatures (which are taken to be the reciprocals of the radii) satisfy the Diophantine equation Here, the circles are supposed to have no common interior point which means by convention that the outermost circle’s exterior is the interior and the interior is the exterior and the radius is negative. Thus, if we are given 3 of the circles and they have integer curvatures, the fourth must also have integral curvature because of the equation! In the figure here, the curvatures are .

ABC-conjecture

The ABC conjecture - formulated independently by Masser and Oesterl´e - supercedes many conjectures in Diophantine equations and implies many of them. It formalizes the intuitive observation that when two numbers and are divisible by large powers of small primes, then tends to be divisible by small powers of large primes. More precisely:

“For any , there are only finitely many triples of relatively prime integers satisfying , and , where is the product of all distinct prime divisors of .”

For instance, the ABC-conjecture implies Fermat’s last theorem for sufficiently large exponents; in fact, it implies finiteness of the number of solutions of the generalized Fermat equation . There is the as-yet-unsolved Beal’s conjecture (also known as the Tijdeman- Zagier conjecture); until it is actually solved, one cannot predict what methods will work. The conjecture asserts that for implies that must have a common prime factor, and was formulated in 1993 by Andrew Beal, a banker and amateur mathematician.

One of Beal’s goals is to inspire young people to think about the equation, think about winning the offered prize, and in the process become more interested in the field of mathematics. The prize money - now a million dollars - is being held by the AMS until it is awarded. The spendable income from investment of the prize money is used to fund the annual Erd¨os Memorial Lecture and other activities of the American Mathematical Society.

The conditions are necessary as shown by the examples

Finally, we would like to mention that we have not discussed some other topics that involve the name of Diophantus. One is an unsolved problem that goes under the name of Diophantine tuples (both integer and rational) problem. Diophantus himself found a rational -tuple . The question as to how large a set of positive rationals can be found so that all are squares for is still open? For integer tuples, is the limit as was proved in 2016. Another fertile area of current research involves the so-called Frobenius Coin exchange problem: “Given positive integers with no common factor , what is the largest integer that cannot be represented as a nonnegative integral linear combination of the given integers?” Finally, we only alluded to briefly while describing a rational approximation to , the very rich subject of Diophantine approximation which is at the heart of many modern developments in number theory and ergodic theory. Maybe, that is for another Pi Day or Ramanujan Day.

References

- A. Granville, T.J. Tucker, "It’s as easy as abc", Notices A.M.S. (2002), 1224-1231.

- L.J. Mordell, "Diophantine equations", Academic Press 1969.

- R. C. Baker, "Diophantine inequalities", Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1986.