The Genius of Koshliakov and His Indomitable Spirit

Introduction

“The humankind has regularly witnessed the birth of influential personalities who have

time and again guided people through difficult situations and have raised their spirits.

Adversities or ordeals could not crush them, and instead, they emerged victorious

through their heroic deeds.”

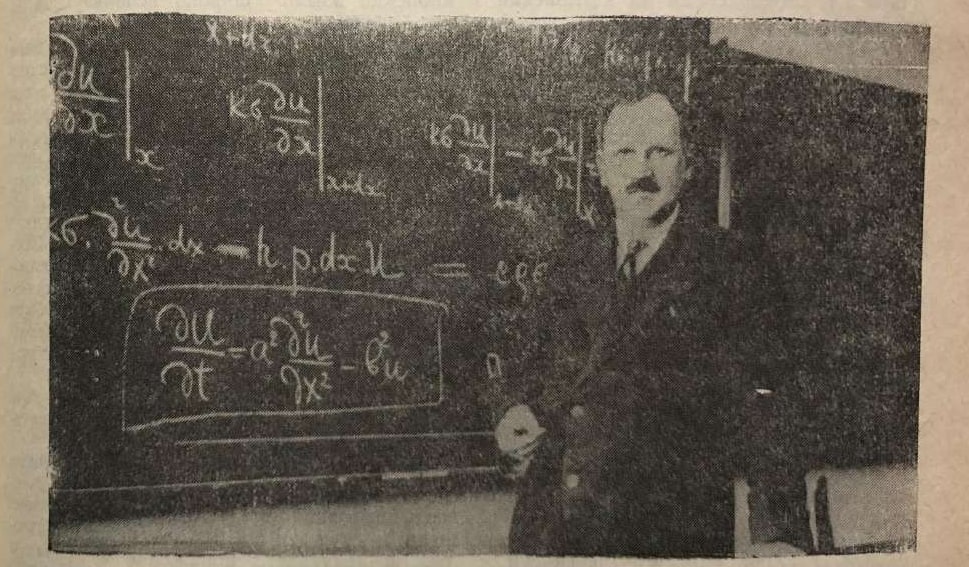

One such role model that we will see in this article is the Russian mathematician Nikolai Sergeevich Koshliakov1. Koshliakov was born on 11th July 1891 in St. Petersburg, Russia. After finishing his gymnasium (high school and college), Koshliakov entered the Department of Physics and Mathematics at St. Petersburg University, graduating in 1914 with a diploma securing a first class. Before being accepted at St. Petersburg, Koshliakov had mastered differential and integral calculus on his own [1] (see also [10]).

At the university, he was taught by excellent mathematicians such as Markov, Steklov, Uspenskii etc. He became interested in analytic number theory, heavily influenced by the work of G. F. Voronöı. After graduation, he remained at St. Petersburg for his Masters. Throughout his life, Koshliakov held several eminent positions at various universities. He was an excellent teacher, his lectures being precise and comprehensible. His textbook on differential equations [6] became greatly popular among students, the outgrowth of which is [9].

Koshliakov was a researcher par excellence who mainly worked in analytic number theory and differential equations. He published more than 65 papers ranging from summation formulas to problems in applied mathematics. His slick proof of the Voronöı summation formula [4] is, according to the present author, the shortest proof known so far and full of ingenuity!

The subject of this note is concerned with one manuscript written in Russian by Koshliakov [7], whose title translates to ‘A study of a class of transcendental functions defined by the generalized Riemann equation’. But before we delve into it, it is important to understand the political situation in Soviet Union and the conditions in which Koshliakov wrote it.

Political situation in the Soviet Union during World War II, Koshliakov’s arrest, and mathematics from jail

NKVD was the Soviet Union’s secret police organization from 1934 to 1946. During the World War II, Axis powers undertook the “Siege of Leningrad”, a military blockade, from 1941 to 1944. In [1], the authors write

The repressions of the thirties which affected scholars in Leningrad continued even after the outbreak of the Second World War. In the winter of 1942 at the height of the blockade of Leningrad, Koshlyakov along with a group … was arrested on fabricated … dossiers and condemned to 10 years of correctional hard labour. After the verdict he was exiled to one of the camps in the Urals. … On the grounds of complete exhaustion and complicated pellagra, Koshlyakov was classified in the camp as an invalid and was not sent to do any of the usual jobs. … very serious shortage of paper. He was forced to carry out calculations on a piece of plywood, periodically scraping off what he had written with a piece of glass. Nevertheless, between 1943 and 1944 Koshlyakov wrote two long memoirs Issledovanie nekotorykh voprosov analyticheskoi teorii rational’nogo i kvadratichnogo polya (A study of some questions in the analytic theory of rational and quadratic fields)1 and Issledovanie odnogo klassa transtsendentnykh funktsii, opredelyaemykh obobshchennym yravneniem Rimana (A study of a class of transcendental functions defined by the generalized Riemann equation).

Further details are given in [11, p 211–213], where the author says that the main purpose of the NKVD was to obtain signed “confessions”2 from the accused as proofs of their guilt (of supporting the Axis powers). Koshliakov wasn’t the only one. In fact, he was one among 13 scientists and mathematicians who were considered as the accused. Lorentz [11, p. 212] says,

By April 1942, after seven hungry months, the accused were suffering from acute starvation; many of them had lost of their normal weight and were close to death. It is humanly understandable that an offer of a bowl of soup was sufficient to force them to sign a “confession”, an ultimate proof of guilt. Forced to stand for hours was another form of torture. No wonder that Koshlyakov signed:”I intended to establish relations with the German commandant… I would like to atone for my guilt, be it in a small measure, by participating in our working front…. In particular, would be very happy to complete my work on summation formulas which I have been conducting for years….’

It is not our intention to delve a lot into politics but rather to put forth before everyone (especially students), how, in the extreme predicament that Koshliakov was going through, he could maintain his scientific fervour and produce magnificent research!

My “discovery” of Koshliakov’s second manuscript written from jail: A personal story

The second manuscript which Koshliakov wrote from jail under his patronymic name N. S. Sergeev, namely, [7], although published, can still be considered as “lost” since nobody (except for a passing reference to it in the thesis of A. G. Kisunko [3, p. 4]) studied its contents for 70 years! I had the good fortune of “discovering” it in 2010 while I was a fourth year PhD student in Mathematics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Since this episode might be interesting to some of you, let me take some liberty to explain how it unfolded. I happened to come across the article [1] written on the centenary of Koshliakov’s birth, where I first learned of his second manuscript [7]. The authors of [1] had discussed in it some of the contents of [7]. I was taken aback to see an integral involving the Riemann -function considered there which generalized an integral considered by Ramanujan in his published paper [12].

I was happy and anxious, at the same time, to see the manuscript [7], and decided to get hold of it, and also everything else that Koshliakov had published. This is because I, myself, was working on a generalization of that very same integral of Ramanujan, and so I wanted to make sure that I am not replicating what Koshliakov did years ago! The manuscript was available at the Center for Research Libraries (CRL) in Chicago. I asked the UIUC Math librarian Tim Cole if we could get it for a few days via inter-library loan. I was pleasantly surprise to find that the CRL had scanned the -page manuscript and had emailed it to me! To my solace, Koshliakov had not done anything I was working on. I found the manuscript to be very interesting though.

However, it wasn’t until ten more years that I decided to seriously study this manuscript along with my PhD student Rajat Gupta. It was then that we found out what a gem this manuscript is! We made two modest contributions to the theory [2].

Contents of the manuscript

To describe the main idea, let us first define the Riemann zeta function, one of the most important functions of mathematics. For , it is defined by the absolutely and uniformly convergent series

It can be analytically continued to the entire complex plane except for a simple pole at . Koshliakov’s theory stems from a problem in Physics on heat conduction. We refer the reader to [5] and [6, p. 488-489] for a description of this problem.

The equation where , forms the crux of Koshliakov’s theory. It is the characteristic equation of the generalized heat equation encountered by Koshliakov in his problem on heat conduction. As , the positive roots of the characteristic equation are (being the roots of the resulting equation ). Thus, in this special case, the series is nothing but the Riemann zeta function . Moreover, when and , we get , which implies that the positive roots are .Thus, one can study the series

For any , one may then construct a general zeta functionfor . In fact, Koshliakov considers a normalized version of this series, namely,

This is one of the two Koshliakov zeta functions. With this foundation, Koshliakov shows unmatched brilliance in developing the theory of these zeta functions and the functions associated to them. For details, the reader is referred to [7] and [2].

Concluding remarks

Koshliakov died of a brain haemorrhage on 23rd September 1958. While mortal remains put an end to a person’s physical presence, the ideas he/she comes up with live forever. Koshliakov’s legacy and his indomitable spirit will continue to inspire everyone as long his mathematics is studied!

Acknowledgements

The author’s research is funded by the Swarnajayanti Fellowship grant SB/SJF/2021-22/08 of ANRF (Government of India) as well as by the N Rama Rao Chair Professorship at IIT Gandhinagar. He sincerely thanks both for their support.

References

- N. N. Bogolyubov, L. D. Faddeev, A. Yu. Ishlinskii, V. N. Koshlyakov and Yu. A. Mitropol'skii, _Nikolai Sergeevich Koshlyakov (on the centenary of his birth)_, Uspekhi Mat. Nauk *45* (1990), No. 4, 173--176; English transl. in Russian Math. Surveys *45* (1990), No. 4, 197--202.

- A. Dixit and R. Gupta, _Koshliakov zeta functions I: Modular relations_, Adv. Math. *393* (2021), 108093 (41 pages).

- A. G. Kisunko, _Zeta functions and their application to solving some problems of mathematical physics_ (Russian), Dissertation, Moscow State Institute, 1999.

- N. S. Koshliakov, _On Voronoi's sum-formula_, Mess. Math. *58* (1929), 30--32.

- N. S. Koshliakov, _An extension of Bernoulli's polynomials_, Mat. Sb. *42* no. 4 (1935), 425--434.

- N. S. Koshlyakov, _Basic Differential Equations of Mathematical Physics_, ONTI, 4th edition, 1936.

- N. S. Koshliakov (under the name N.S. Sergeev), _Issledovanie odnogo klassa transtsendentnykh funktsii, opredelyaemykh obobshcennym yravneniem Rimana_ (A study of a class of transcendental functions defined by the generalized Riemann equation) (in Russian), Trudy Mat. Inst. Steklov, Moscow, 1949. (Available online at https://dds.crl.edu/crldelivery/14052)

- N.S. Koshliakov, _Investigation of some questions of the analytic theory of rational and quadratic fields_, I, II and III (in Russian), Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Mat. *18* No. 2, 113--144; No. 3, 213--260; No. 4, 307--326 (1954).

- N. S. Koshlyakov, M. M. Smirnov and E. B. Gliner, _Differential Equations of Mathematical Physics_, North-Holland Publishing Co., Amsterdam; Interscience Publishers John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1964. xvi+701 pp.

- V. N. Koshlyakov, O. A. Ladyzhenskaya and D. R. Merkin and M. M. Smirnov, _Nikolai Sergeevich Koshlyakov (on the centenary of his birth)_ (Russian), Vestnik Leningrad Univ. Mat. Mekh. Astronom. (1991) No. 4, 81--83.

- G. G. Lorentz, _Mathematics and Politics in the Soviet Union from 1928 to 1953_, J. Approx. Theory *116* (2002), 169--223.

- S. Ramanujan, _New expressions for Riemann's functions $xi(s)$ and $Xi(s)$_, Quart. J. Math. *46* (1915), 253--260.