Patterns In Primes Via Probability

Introduction

The idea of a number lies at the very foundation of human civilization. Some of the earliest archaeological records of writing already reveal an awareness of natural numbers, marking a crucial step in the development of abstract thought. Reflecting on this, R. Dedekind famously wrote that "numbers are free creations of the human intellect; they serve as a means of grasping more easily and more sharply the diversity of things". Since numbers provide a lens through which we interpret the world, their study has fascinated mathematicians for centuries.

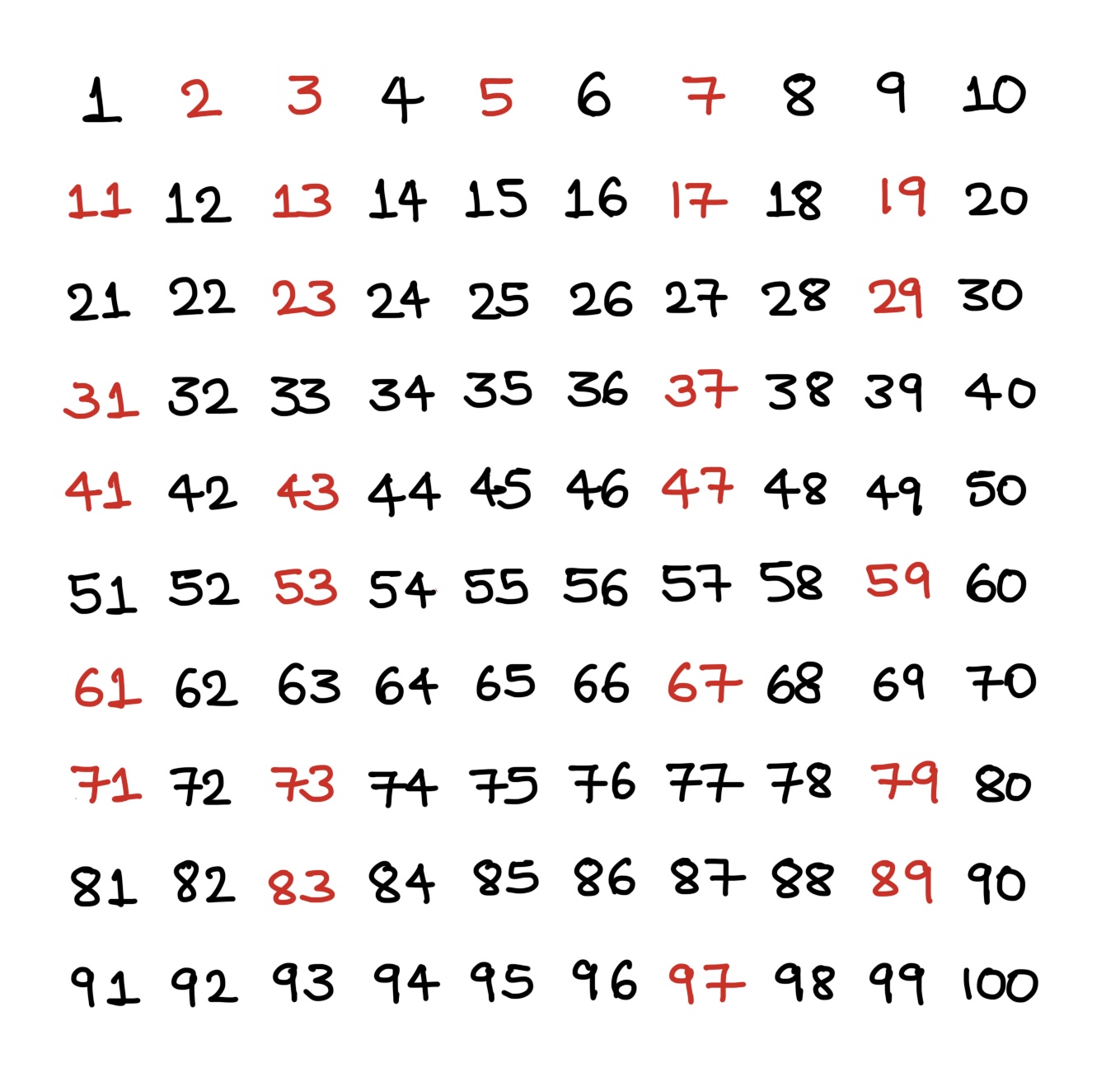

One of the earliest and most profound discoveries in mathematics, dating back to Euclid, is that every natural number can be written as a product of prime numbers. In this sense, primes serve as the fundamental building blocks of arithmetic. A prime number is a natural number that has no divisors other than and itself. For instance, , , , , and are prime, whereas is not. The study of prime numbers has attracted many of the greatest mathematicians, including Euler, Gauss, Dirichlet, and Riemann.

One of the first striking facts about primes is Euclid’s theorem asserting that there are infinitely many of them. Yet even a brief inspection of the primes among the first natural numbers reveals an apparent lack of regularity. Aside from the trivial observation that all primes except are odd, no simple pattern emerges. It is therefore unsurprising that there is no fast and fully deterministic procedure for locating very large primes. Indeed, the largest known prime as of December 2025 is a number discovered through extensive computation rather than a simple formula.

Despite this apparent irregularity, prime numbers exhibit remarkable statistical regularities. In the late eighteenth century, Adrien-Marie Legendre and Carl Friedrich Gauss independently observed, based on extensive numerical evidence, that the number of primes up to a large number satisfies Gauss further suggested that primes occur near a large number with density approximately , leading to the refined approximation known as the logarithmic integral. This approximation is surprisingly accurate: for example, there are exactly primes below , while , an error of only about .

This observation, now known as the Prime Number Theorem, was proved independently by Jacques Hadamard and Charles Jean de la Vall'ee Poussin in 1896, building on ideas introduced earlier by Riemann. Thus, although primes may appear erratic, their overall distribution follows a precise and elegant law.

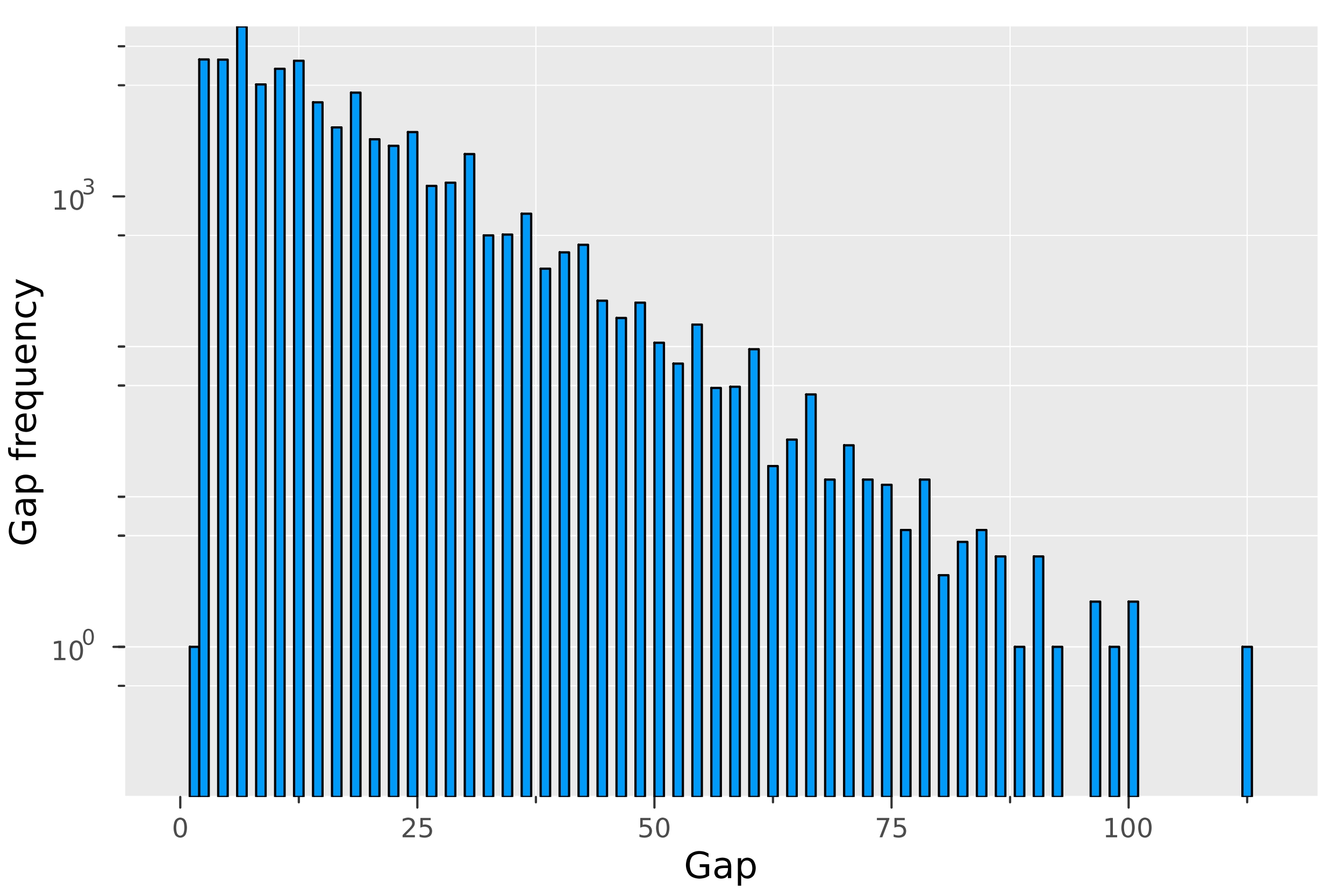

Still, the intuition that primes behave in many ways like an unpredictable sequence remains useful. In this article, we explore how this perspective can lead to meaningful predictions, focusing in particular on the behavior of gaps between consecutive primes. The smallest possible gap is , as seen in twin primes such as or . On the other hand, by considering the numbers one can construct arbitrarily long stretches of composite numbers, and hence arbitrarily large gaps between primes. This naturally raises the question: near a large number , what should a typical gap between consecutive primes look like?

To investigate this, consider an interval , where is large and is much smaller than , but still large enough to contain many primes. The Prime Number Theorem predicts that the number of primes in this interval is approximately Dividing the length of the interval by the number of primes it contains suggests that the average gap between consecutive primes near is about . This reasoning also reinforces Gauss’s original insight that roughly one out of every numbers near is prime.

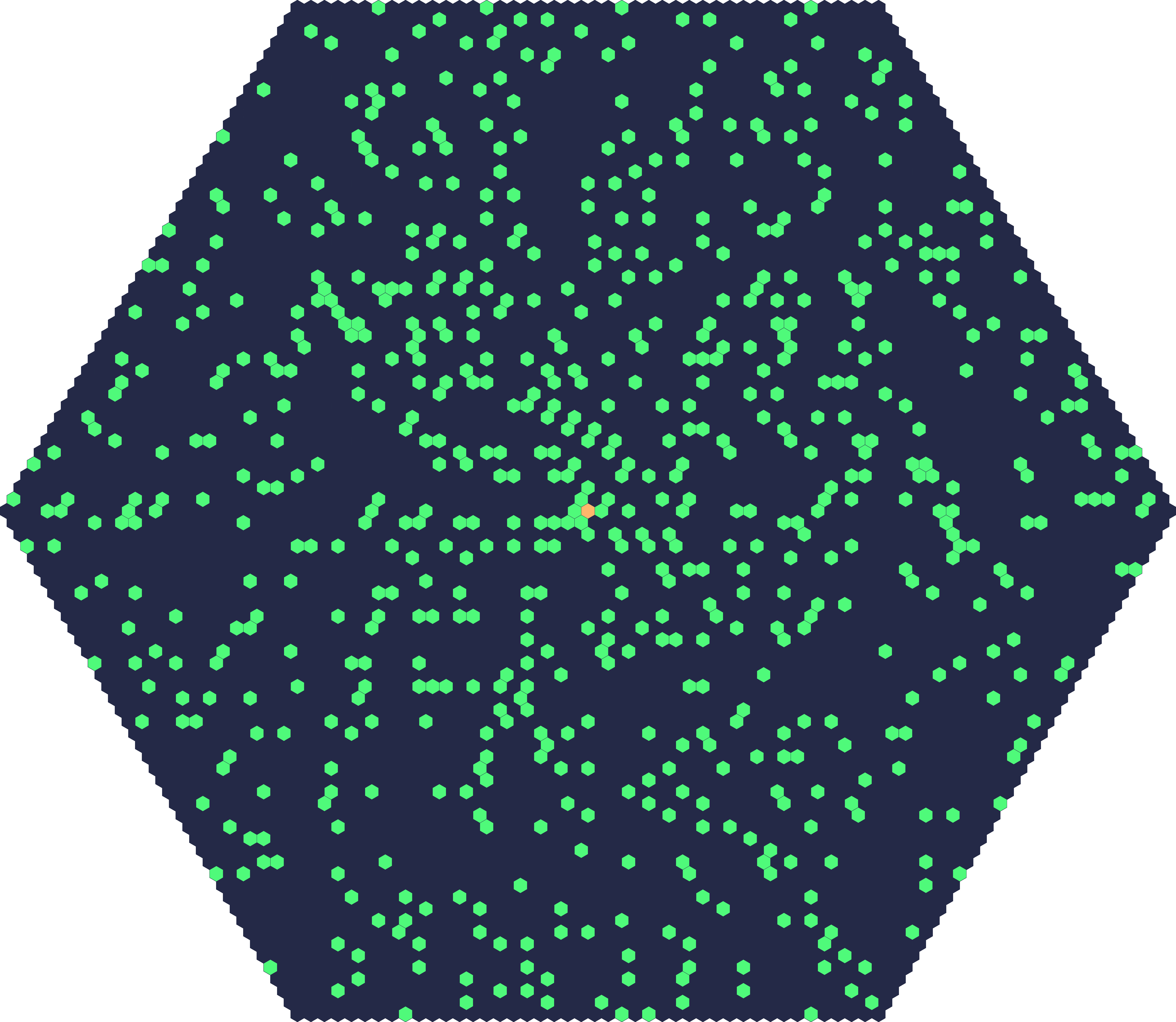

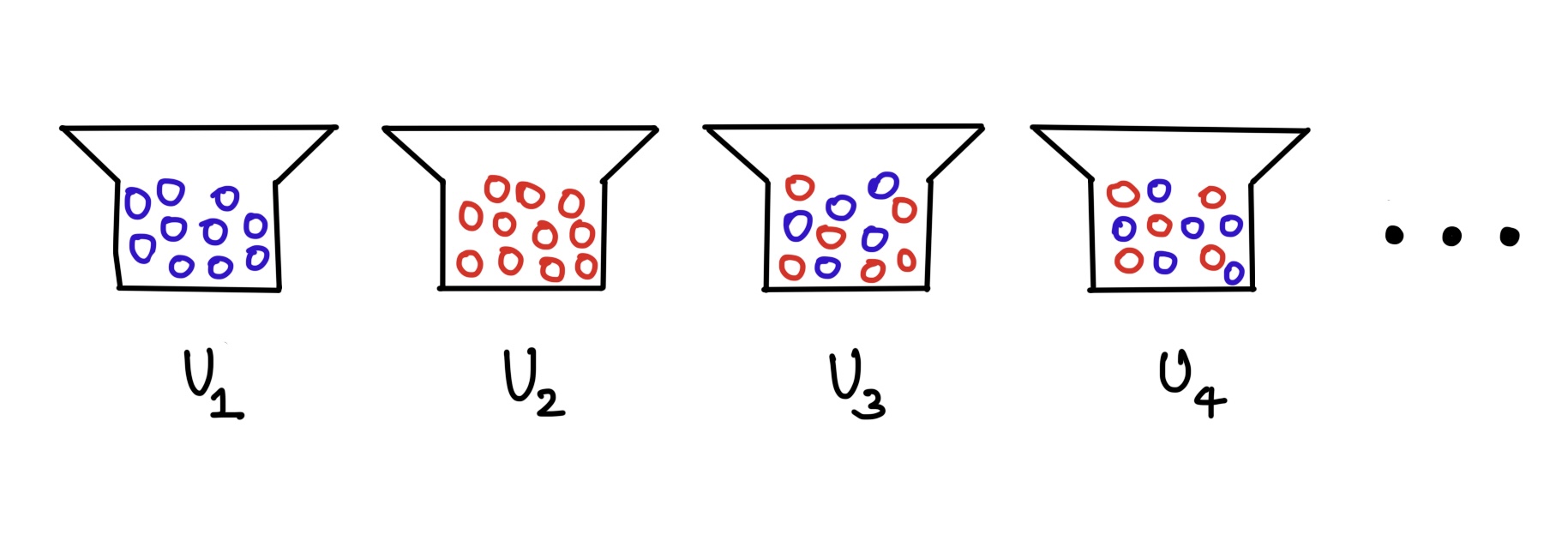

This line of thought inspired the Swedish mathematician Harald Cramér in 1936 to introduce a probabilistic model for primes. Imagine an infinite sequence of urns The urn contains only blue balls, only red balls, and for , the urn contains both colors. Suppose that when drawing a ball from , the probability of obtaining a red ball is . Drawing independently from each urn produces an infinite sequence of red and blue outcomes. Let denote the index of the urn from which the -th red ball is drawn. The resulting sequence is increasing and serves as a model for the sequence of prime numbers.

If we define then

This mirrors the behavior of , reinforcing the analogy between and the primes. In particular, one may expect the largest gaps between primes to resemble the largest gaps between successive .

Using results from probability theory, Cramér showed that with probability one, Motivated by this, he conjectured that prime gaps satisfy a similar bound.

Conjecture 1 (Cramér’s Conjecture)

Let be the sequence of prime numbers.

Although powerful, Cramér’s model is undeniably simplistic. It ignores basic arithmetic constraints, such as the fact that all primes except are odd, or that no number divisible by can be prime. Consequently, relying on the model without modification can lead to misleading predictions.

A striking example concerns twin primes—pairs of primes . While it is widely believed that infinitely many twin primes exist, this remains unproven. Cramér’s model predicts that the number of twin primes up to should be approximately However, the same reasoning would predict a similar number of consecutive primes, which is clearly impossible beyond the pair . This illustrates the limitations of the model.

Nevertheless, when refined to account for divisibility by small primes, Cramér’s framework yields more accurate predictions. Granville showed that such corrections replace the constant in the strong conjecture with , where is Euler’s constant. Similarly, the refined model predicts that the number of twin primes up to should be

Cramér’s model also sheds light on the distribution of primes in short intervals. Under this framework, intervals with typically contain about primes. In 1943, assuming the Riemann Hypothesis, A. Selberg showed that this holds for almost all such intervals. For many years, it was believed that this behavior should hold uniformly. However, in a groundbreaking result, H. Maier demonstrated in 1985 that there are infinitely many short intervals where the number of primes deviates significantly from this expectation.

Seen in this light, Cramér’s model reveals both the power and the limitations of probabilistic reasoning in number theory. It captures the correct scale of prime gaps while falling short of fully encoding arithmetic structure. Its successes and failures together show why such models are best viewed as guiding principles rather than final answers. By exploring where the model works, where it breaks down, and how it can be refined, mathematicians continue to uncover subtle patterns beneath the surface, ensuring that the study of prime numbers remains a vibrant and evolving field.